When it comes to understanding eyewitness memory, people’s commonsense views are sometimes consistent with contemporary scientific knowledge – but sometimes they are dangerously adrift. This article aims to unravel some of the common myths that appear in the courts, in the news, and in the awareness of the public.

On a mid-summer evening in 1982, in a small town in the southern U.S., 24-year-old Susan1 was walking home, when a man grabbed her, threatened her with a gun, forced her into the woods, and brutally beat and raped her over several hours. The young, white victim reported key details of the rapist to investigators (a black man with short hair and a thin moustache), and later identified the police suspect from a photographic lineup, becoming visibly distressed when she encountered his picture. When Susan took the stand at trial to detail the traumatic events of her violent rape, her disturbing testimony and confident identification convinced the court to serve justice and protect society by locking away the defendant for life. Unfortunately, this victim made a mistake and identified an innocent man. Her mistake, later contradicted by DNA evidence, helped imprison Marvin Anderson for 15 years (Gould, 2007).

This case highlights the dilemmas inherent in eyewitness evidence. Firstly, our unavoidable reliance on eyewitness testimony is pitted against the dangerous consequences of human error. To date, there have been 330 DNA exonerations of wrongfully-convicted innocent persons in the U.S., 235 (72%) of which involved eyewitness misidentification (Innocence Project, 2015). Although TV shows like CSI suggest otherwise, “hard evidence” is only available in a minority of criminal cases. Indeed, most of these exonerated innocents were able to be proven innocent because they had been convicted of murder or sexual assault – the subset of crimes that often do leave behind testable biological traces (Wells, Memon, & Penrod, 2006). But even in the fraction of crimes where police can successfully link evidence like fingerprints and DNA to a suspect, the testimony of an eyewitness is still needed to connect that evidence to the heist. Are your fingerprints at the scene of a bank robbery because you are a local client or because you were involved in the crime? In other words, even in the minority of cases where technical evidence does exist, that evidence requires interpretation, and witnesses play a vital role in that interpretation.

Secondly, in the history of eyewitness evidence, public opinion and legal minds have extolled it as the very best tool of the justice system and also rejected it as the very worst. After the arrest of a 19-year old suspected of fatally stabbing another man, a California Police Chief (U.S.) praised eyewitness evidence, stating, “We wouldn’t have solved this tragic crime so quickly without the support of our law enforcement partners and the cooperation of many witnesses,” (McMenamin, 2015). On the other hand, a Scottish court recently opined that, when the prosecution depends on eyewitness identification, “the risk of a miscarriage of justice is notorious,” (Gage v. HM Advocate, 2011).

Consequently, eyewitness evidence is suspended in a middle ground, where legal professionals, journalists, and the public both rely on it and discard it. Meanwhile, in neglecting to apply existing scientific knowledge, both lay and professional evaluators demonstrate little ability to discriminate reliable from unreliable evidence. Common misconceptions surrounding eyewitness memory lie at the center of these conflicts and contribute to devastating failures within the justice system– both the wrongful conviction of innocents and the failure to apprehend and/or convict actual perpetrators. Unraveling such myths is necessary in order to develop a balanced view on the strengths and limitations of this type of evidence.

Myth #1: All Eyewitnesses Are Unreliable

This is a sentiment that is often expressed in media articles detailing the pitfalls of eyewitness evidence in courts and highly-publicized examples of wrongful convictions. However, it is simplistic and counterproductive to write eyewitnesses off as entirely unreliable. Cases are often solved with the help of eyewitnesses, whether through investigatory leads, or identification of suspects. In fact, a review of factors that led to the resolution of 189 re-opened cold cases for the District of Columbia’s Metropolitan Police Department (U.S.) showed that a majority of the cases solved were a result of new eyewitnesses coming forward (63%), significantly more than by DNA testing (3%; Davis, Jensen, Burgette, & Burnett, 2014).

In reality, most eyewitnesses are reporting crimes about people they know- such as the approximately 90% of female rape and serious sexual assault victims in the UK who knew the perpetrator prior to the offence (Ministry of Justice, Home Office, & the Office for National Statistics, 2013). Psychological experiments intentionally create suboptimal conditions for eyewitness recall and identification in order to demonstrate how bad we can be in certain situations. These situations – including unfamiliar perpetrators, poor lighting conditions, and/or biased lineups – are the kinds of situations in which wrongly-convicted innocents find themselves misidentified. This does not mean that all eyewitnesses are unreliable; it means that eyewitnesses, under certain conditions, can make mistakes that any of us could make under the same conditions.

Even though Susan was mistaken in her identification, she is an example of a seemingly-credible witness. She provided an accurate description of the perpetrator, reported valuable information, including the assailant’s claim that he had a white girlfriend, and identified his silver bicycle. A local with a history of assault that matched the reported characteristics, later confessed to the rape. She was not a “bad” witness, but a well-intentioned and helpful one, who understandably put her trust in the police agents guiding her through the investigation. Unfortunately, she was attempting to identify a man of a different race from a biased lineup (Anderson’s was the only color photo placed among black-and-white mugshots). By the time the trial took place, Susan had been exposed to a multitude of variables known to have adverse effects on eyewitness memory. As a consequence, her ability to make an accurate identification during the investigation and a fair assessment of her stated confidence during the trial in that identification was impaired.

The memory of eyewitnesses is malleable, and their reconstructions are dependent on a complex interplay of personal, situational, and social factors (e.g., the witness’ distance from the perpetrator, individual memory-strength, interviewing techniques). It is crucially important for those involved in criminal cases to engage in understanding such factors that may impact memory and to critically evaluate the evidence presented, rather than blindly accepting or indiscriminately rejecting eyewitnesses.

Myth #2: Everyone Knows When Eyewitnesses Are Unreliable

Many of the high-profile exoneration cases, such as the Anderson case above, emerged from crimes committed and tried in a time when DNA testing was virtually unheard of. Today, cases like Anderson’s have fixed a media spotlight on causes of wrongful convictions and external influences on eyewitness evidence, and we have decades of psychological research on eyewitness memory. Some European countries and a handful of states in the U.S. have adopted identification procedures to align with scientific recommendations.

Yet biased lineups and erroneous identification are still a significant risk. A case in point is that of Henry Osagiede, a Nigerian native who was convicted of robbery and sexual assault in Spain in 2008 (Epifanio v. Madrid, 2009). Both victims, who described the assailant as a black man, identified Osagiede from a live lineup with complete certainty. Based on this evidence, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison. The Spanish Supreme Court overturned the conviction a year later when it came to light that the convicted man was identified from a biased identification procedure: Placed among four Latin-Americans, Osagiede was the only black man in the lineup.

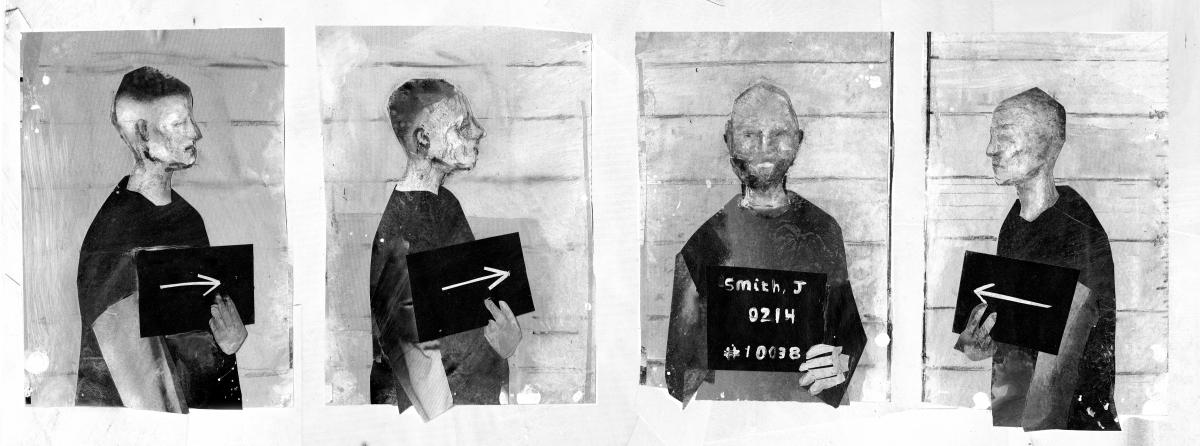

In the lab, psychologists demonstrate how seemingly-harmless decisions in constructing a lineup can easily bias someone to choose the suspect - whether that suspect is guilty or not. Lineup fairness can be assessed by providing non-witnesses (people who are ignorant to the identity of the perpetrator) with a description of the perpetrator and then asking them to pick out the lineup-member that best matches that description (Doob & Kirshenbaum, 1973). If the lineup is fair, responses should be evenly spread among the lineup members presented. This is what the Eyewitness Identification Research Laboratory at the University of Texas (El Paso) did with the lineup of a perpetrator described as an African-American, male teenager with long, braided hair (n.d.). Although the lineup was constructed with six African-American teens, 95% of non-witnesses managed to pick out the police suspect - the only person with braided hair. In this case, a positive identification only demonstrates that the eyewitness is able to identify the most reasonable option. Unfortunately, juries and judges often only see the final result of a police identification lineup. Without the relevant background information or documentation of the actual lineup, there is no real means of judging the reliability of a positive suspect identification.

In cases like Osagiede, it is clear that influences proven to impact the ability of eyewitnesses to make accurate identifications were not considered. Even more alarming is when such influences are not revealed to or considered by judges and juries making life-altering decisions to convict or acquit the accused. Perhaps “everyone knows” that eyewitnesses can be inaccurate, but it can easily be forgotten, ignored, or lost in translation when applied to investigatory and legal decision-making.

Myth #3: Consistency Is the Hallmark of the Reliable Witness

In the legal arena, consistency is considered a vital means of determining witness credibility. Police officers intuitively distrust accounts that change from one telling to the next (Krix, Sauerland, Lorei, & Rispens, 2015) and lawyers use inconsistencies to discredit a witness on the stand (Fisher, Brewer, & Mitchell, 2009). In fact, juries in the U.S. are instructed to use statement consistency as a critical factor in determining the credibility of an eyewitness. However, inconsistencies appear any time we rely on memory, and are not necessarily evidence of a defective or deceptive witness.

In the spring of 2011, six-year-old Vicky1 witnessed the murder of her mother (Brackmann, Otgaar, Sauerland, & Jelicic, 2015). When police, responding to neighbors’ reports of domestic disturbances next door, arrived at the house, Vicky answered the door and immediately said her father had done it. She was interviewed officially the same day, and she repeated her allegation that her father was the murderer. Two months later, she was questioned a second time. She again blamed her father, but this time produced new details about how the crime was committed, including the murder weapon used (a knife). Since the father denied the crime, Vicky became a key witness against him.

Imagine now a typical courtroom tactic in which the defense cross-examined Vicky on the stand. Given that statement inconsistency is used as a means of determining a credible witness, lawyers would likely pursue these new details to suggest that Vicky was unreliable, had been given external information, or had made up a story to explain the traumatic death of her mother. However, when we report about an event several times, as witnesses are often required to do, it is not unusual for different information to appear across accounts.

When inconsistencies do arise, they can be details that are a) initially reported and later changed (contradictory), b) reported in an earlier interview, but not a later one (forgotten or non-reported), or c) initially not reported, but reported later (reminiscent). Despite general suspicion that all inconsistent details reflect unreliability, reminiscent and forgotten details themselves tend to be as accurate, or only slightly less accurate, than consistent ones (Krix et al., 2015; Oeberst, 2012). Furthermore, inconsistencies across statements show little to no relationship with the accuracy of the overall account (Smeets, Candel, & Merckelbach, 2004).

Discrepancies in recall across interviews can be attributed to a number of factors, including asking a witness different questions than the first time (Fisher et al., 2009), or even asking the same questions again (e.g., Erdelyi & Becker, 1974). We often experience this when we tell stories from years-past and have forgotten some details or suddenly recall a detail once-forgotten. Consistency may be valued in the courtroom, but entirely discounting a witness that provides some inconsistent details ignores natural variations in memory recall.

Myth #4: The More the Merrier! If Several Witnesses Say It, It Must Be True.

Kirk Bloodsworth, the first man to be exonerated from Death Row in the U.S., was convicted of the rape and murder of a child in 1984, based on the testimony of five eyewitnesses (Junkin, 2004). Osagiede, the Nigerian native, was also identified by two victims. Both cases were prosecuted entirely based on the testimony of multiple eyewitnesses expressing absolute certainty in their identifications – yet both convictions were ultimately overturned at least in part due to unreliable identifications.

The contribution of multiple witnesses to confirm the events of a crime or identify a suspect inspires confidence in the “facts” presented. Perhaps we can suspect one person’s memory of being faulty, but would five witnesses give the same version of events if it wasn’t true? However, multiple corresponding witness reports do not guarantee accuracy: in a review of 190 exonerees’ transcripts, 36% of the wrongfully-convicted innocents had been identified by multiple eyewitnesses (Garrett, 2011). Ultimately, any memory of a witnessed event is susceptible to external influence, regardless of how many eyewitnesses there are. In the case of Bloodsworth, one of the two boys that saw the victim walk off with the perpetrator identified him immediately from the police lineup. The other boy originally identified a different man, but his mother called two weeks later to report that he had been too afraid to identify Bloodsworth at the time. Several of the other witnesses had independently seen him pictured in handcuffs on the evening news before identifying him in the lineup. The five witnesses had separately arrived at convictions of Bloodsworth’s guilt in different ways, and there is no obvious evidence to suggest that these witnesses influenced each other. However, each of them may have been affected by various factors that influenced their decisions, and they all eventually managed to (inaccurately) confirm the police suspect and build a convincing case for the prosecution.

Each of multiple witness reports are not only independently vulnerable to the same external influences as all eyewitness evidence, but are also susceptible to the influence of the other witnesses. In the UK, 88% of surveyed witnesses to a crime reported the presence of co-witnesses, more than half of whom had discussed the crime and suspect details with other witnesses (Skagerberg & Wright, 2008). While it is quite understandable that after having observed an upsetting event witnesses want to share their impressions, the pitfall of such conversations is that witnesses can influence each other’s recollections. If witnesses come to know what another has said, they can unconsciously insert these details into their own memory of the event, or leave out important details (Merckelbach, van Roermund, & Candel, 2007). As a result, co-witnesses may (inadvertently) come up with a common version of events – often the version provided by the most confident witness (Wright, Self, & Justice, 2000).

While no study has specifically looked at the possible influence of the number of witnesses on confidence in their stories, we do tend to trust information that comes from multiple (seemingly) independent sources (Harkins & Petty, 1987). Prosecutors take advantage of this by emphasizing that presenting multiple eyewitnesses makes their case particularly strong (Garrett, 2011). However, the mere existence of multiple eyewitnesses telling the same story is not, in itself, proof of accuracy. Multiple witness accounts are reassuring in an investigation, but only if their accounts are both truly independent, and untainted by those very factors to which all eyewitness accounts are vulnerable. Therefore, the reliability of each of these multiple accounts must be subject to the same level of scrutiny as accounts from a single witness.

Myth # 5: All of This Is Just Common Sense

Psychology is often thought of as a science of common sense. In fact, in cases when judges bar eyewitness memory experts from testifying, they often rule that the psychologist cannot offer information outside of general common sense (e.g., State v. Coley, 2000). If media reports and court rulings are any indication, then the concept that eyewitnesses are unreliable appears to be generally considered “common sense”. However, surveys suggest that people don’t understand why they distrust memory or what factors can influence the reliability of memory. For example, only 41% of surveyed jury-eligible Americans believe that lineup instructions can impact the accuracy of an identification and only 50% know that eyewitness confidence in that identification is highly susceptible to outside influences (compared to 98% and 95% of memory experts, respectively; Benton, Ross, Bradshaw, Thomas, & Bradshaw, 2006). We find similar disagreements between lay people and experts regarding how the presence of a weapon impacts encoding and how race plays a role in identification (Houston, Hope, Memon, & Read, 2013). A commonsense distrust of memory is not useful if it fails to distinguish between accurate and inaccurate memories or identify the contextual factors that affect memory reliability. As renowned memory researcher, Endel Tulving, once wrote, “Much of science begins as an exploration of common sense, and much of science, if successful, ends if not rejecting it then at least going far beyond it,” (2003, p. 1,505). Common sense is convenient, but it is not sufficiently or consistently well-informed to guide legal judgments with life-altering consequences.

Conclusion

Whatever media accounts or TV series seem to propose- eyewitness evidence is here to stay. Furthermore, science does not argue that we should exclude eyewitness evidence in court. The science does argue, however, that eyewitness evidence always exists at the center of a web of a number of influential factors - all of which deserve scrutiny throughout all phases of an investigation and trial. In light of the misconceptions regarding memory, experts seek to increase sensitization among legal professionals to variables that impact eyewitness memory, allowing them to obtain more accurate evidence on the one hand, and appropriately evaluate the credibility of the eyewitness and the reliability of the evidence on the other. Failure to do this guarantees more regrettable cases like Anderson’s, where innocent suspects are left vulnerable to wrongful conviction and actual perpetrators are free to continue offending. Of any aspect of the intersection of the justice system and memory, seeking and considering scientific opinion in a realm outside of our expertise is simply an exercise in common sense.

References

Benton, T. R., Ross, D. F., Bradshaw, E., Thomas, W. N., & Bradshaw, G. S. (2006). Eyewitness memory is still not common sense: Comparing jurors, judges and law enforcement to eyewitness experts. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 115-129. doi:10.1002/acp.1171

Brackmann, N., Otgaar, H., Sauerland, M., & Jelicic, M. (2015). When children are the least vulnerable to false memories: A true report or a case of autosuggestion? Journal of Forensic Sciences. Advance online publication. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.12926

Davis, R. C., Jensen, C. J., Burgette, L., & Burnett, K. (2014). Working smarter on cold cases: Identifying factors associated with successful cold case investigations. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 59, 375-382. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.12384

Doob, A. N., & Kirshenbaum, H. M. Bias in police lineups — Partial remembering. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 1973, 1, 287-293.

Epifanio v. Madrid, Spain. Supreme Court (Criminal Division, Section1). [electronic version- database Consejo General del Poder Judicial]. Sentence no: 3687/2009 03 of June [accessed 23 June 2015].

Erdelyi, M. H., & Becker, J. 1974. Hypermnesia for picture: Incremental memory for pictures but not for words in multiple recall trials. Cognitive Psychology. 6, 159-171. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(74)90008-5

Eyewitness Identification Research Laboratory (n.d.). Lineups and evaluations. Retrieved from http://eyewitness.utep.edu/consult02a.html

Fisher, R. P., Brewer, N., & Mitchell, G. (2009). The relation between consistency and accuracy of eyewitness testimony: Legal versus cognitive explanations. In T. Williamson, R. Bull, & T. Valentine (Eds.), Handbook of psychology of investigative interviewing: Current developments and future directions (pp. 121-136). Retrieved from http://www.cti-home.com

Garrett, B. (2011). Convicting the innocent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gage v. HM Advocate [2011] HCJAC 40 at [29], per LJ-C Gill.

Gould, J. B. (2007). The Innocence Commission: Preventing wrongful convictions and restoring the criminal justice system. New York: New York University Press.

Harkins, S. G., & Petty, R. E. (1987). Information utility and the multiple source effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 260-268. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.2.260

Houston, K. A., Hope, L., Memon, A., & Don Read, J. (2013). Expert testimony on eyewitness evidence: In search of common sense. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 31, 637-651. doi:10.1002/bsl.2080

Innocence Project (2015). Retrieved September 10, 2015.

Junkin, T. (2004). Bloodsworth: The true story of one man's triumph over justice. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

Krix, A. C., Sauerland, M., Lorei, C., & Rispens, I. (2015). Consistency across repeated eyewitness interviews: Contrasting police detectives’ beliefs with actual eyewitness performance. PloS One, 10, e0118641. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118641

McMenamin, D. (2015, April 30). 19-year-old man arrested on suspicion of fatal stabbing. Bay City News. Retrieved May 19, 2015, from http://sfbay.ca/

Merckelbach, H., Van Roermund, H., & Candel, I. (2007). Effects of collaborative recall: Denying true information is as powerful as suggesting misinformation. Psychology, Crime & Law, 13, 573-581. doi:10.1080/10683160601160679

Ministry of Justice, Home Office, and the Office for National Statistics. (2013). An overview of sexual offending in England and Wales. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/fi… .

Oeberst, A. (2012). If anything else comes to mind… better keep it to yourself? Delayed recall is discrediting—unjustifiably. Law and Human Behavior, 36, 266-274. doi:10.1037/h0093966

Skagerberg, E. M., & Wright, D. B. (2008). The prevalence of co-witnesses and co-witness discussions in real eyewitnesses. Psychology, Crime & Law, 14, 513-521. doi:10.1080/10683160801948980

Smeets, T., Candel, I., & Merckelbach, H. (2004). Accuracy, completeness, and consistency of emotional memories. The American Journal of Psychology, 117, 595-609. doi:10.2307/4148994

State v. Coley, 32 S.W.3d 831 (Tenn. 2000).

Tulving, E. (2001). Episodic memory and common sense: how far apart?.Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences,356, 1505-1515. doi:10.1098/rsth2001.0937

van Holthoon, F. L., & Olson, D. R. (1987). Common sense: The foundations for social science (Vol. 6). Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Wells, G. L., Memon, A., & Penrod, S. D. (2006). Eyewitness evidence: Improving its probative value. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7, 45-75. doi:10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00027.x

Wright, D. B., Self, G., & Justice, C. (2000). Memory conformity: Exploring misinformation effects when presented by another person. The British Journal of Psychology, 91, 182-202. doi:10.1348/000712600161781

Footnotes

1 Victims described in this article are provided with fictitious names

![US courtroom - Carol M. Highsmith [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons US courtroom - Carol M. Highsmith [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/d9_middle_500_/public/field/image/courtroom_united_states_courthouse_davenport_iowa.jpg?itok=jmoDyMV1)