Human memory is susceptible to errors and distortions. This may sound cliché (Loftus, 2005), but the practical meaning of this is illustrated by, for example, the devastating effects of mistaken eyewitness identifications (Sagana, Sauerland, & Merckelbach, 2012), the far-reaching consequences of innocents who falsely confess to crimes they never committed (Kassin & Gudjonsson, 2004), and the tragedy of adults who erroneously come to believe that they recovered very early memories of abuse experiences (Loftus, 1993). As for these alleged recovered memories: there was a fierce debateamong psychologists, therapists and even legal professionals in the 1990s (Howe & Knott, in press) about their authenticity, a debate that was even characterized as the “memory wars” (Patihis, Ho, Tingen, Lilienfeld, & Loftus, 2014). It took place against a background of hundreds of lawsuits by adults against their parents because of the alleged abuse memories from childhood that had been “recovered” during therapy in adulthood (Lipton, 1999). Some therapists and clinical psychologists argued that such recovered memories are essentially correct and surface after repression has been lifted due to therapeutic interventions (e.g., hypnosis, sedating drugs). Many researchers, however, contended that recovered memories might, in fact, be pseudo-memories produced by risky techniques such as hypnosis and guided imagery (Howe & Knott, in press; Lambert & Lilienfeld, 2007).

One group of individuals who are particularly interesting are those who previously claimed to have recovered a memory of a sexually abusive episode, but later retracted those claims (Ost, Costall, & Bull, 2002). Do these retractors still have “memories” of these abusive episodes? How do these retractors view their earlier experiences? One recent line of investigation that focused on memories and beliefs and how these are related to each other, might provide some clarification. Briefly, this research has revealed that under certain circumstances, people form memories of events but develop doubts about whether the events have actually occurred. Under these circumstances, people still report having vivid images and recollections of an event, but they do not believe that the event actually happened, turning them from false memories into nonbelieved ones.

Nonbelieved memories have previously been assumed to be an extraordinary rare phenomenon (Mazzoni, Scoboria, & Harvey, 2010; Otgaar, Scoboria, & Mazzoni, 2014). Below, we review recent research on nonbelieved memories and show that it has relevance to many areas in psychology (e.g., psychopathology, legal psychology). Before doing so, we will first explain what nonbelieved memories are and will then describe the methods that have been used to experimentally induce them in the lab.

Being Kidnapped and Bombed, but not Believing it

For some time, scholars assumed that nonbelieved memories are a rare phenomenon. Anecdotal descriptions of such memories have occasionally appeared in the literature. For example, the famous developmental psychologist Jean Piaget had a vivid memory of a man attempting to kidnap him when he was two years old. He remembered and described the event in great detail including information that the perpetrator scratched his nurse’s face (Piaget, 1951). However, not until thirteen years later, Piaget’s former nurse confessed that it was she who had fabricated the event and fed the story to him. Piaget no longer believed that he was almost kidnapped as a child, but he could not stop having vivid visualizations and images of the fabricated kidnapping, as if it had still occurred.

For some time, scholars assumed that nonbelieved memories are a rare phenomenon. Anecdotal descriptions of such memories have occasionally appeared in the literature. For example, the famous developmental psychologist Jean Piaget had a vivid memory of a man attempting to kidnap him when he was two years old. He remembered and described the event in great detail including information that the perpetrator scratched his nurse’s face (Piaget, 1951). However, not until thirteen years later, Piaget’s former nurse confessed that it was she who had fabricated the event and fed the story to him. Piaget no longer believed that he was almost kidnapped as a child, but he could not stop having vivid visualizations and images of the fabricated kidnapping, as if it had still occurred.

Nonbelieved memories are fascinating, if only because the bulk of studies focusing on memory examine believed memories: memories of events for which people also believe that the event occurred (Scoboria, Mazzoni, Kirsch, & Relyea, 2004). While various ideas about memory suggest that memories are typically believed to be true (e.g., James, 1890/1950; Brewer, 1996), it is only recently that memory researchers have started to investigate the possibility that memory might exist without accompanying belief.

Are Nonbelieved Memories Really Rare?

In the first systematic study looking into nonbelieved memories, the frequency and characteristics of nonbelieved memories were surveyed. Almost 25% of the 1593 participants reported to have experienced a nonbelieved memory (Mazzoni, Scoboria, & Harvey, 2010). For example, one participant recollected that he had seen a dinosaur although the belief in the event had vanished. Another person reported a childhood memory of a car accident, but many years later discovered that it actually happened to his brother. Memory characteristics, such as visual details, of nonbelieved memories were also examined. Nonbelieved memories did not differ from believed memories in terms of visual characteristics, clarity, richness, and feeling of reliving, which may explain why nonbelieved memories “feel” so authentic.

Some researchers argued that studies like the one of Mazzoni and colleagues (2010) rely on directly asking participants about a typical experience and in this way reveal the purpose of the inquiry. If participants know what the researcher is interested in, then that can artificially inflate the rate of nonbelieved memories. In order to understand the nature and frequency of nonbelieved memories in everyday autobiographical memory, Scoboria and Talarico (2013) used an indirect cueing method, without artificially drawing participants’ attention to nonbelieved memories. Participants were asked to recall events from different ages and then rated the degree of event recollections (memory) and belief in the occurrence of events (belief) on 1-8 point scales. Surprisingly, with this indirect cueing procedure, only 3% to 6% of the events recalled were nonbelieved memories, a much lower rate than the 25% reported by Mazzoni et al. (2010).

What explains the discrepancy in frequency of nonbelieved memories elicited by direct and indirect cueing methods? Well, perhaps there is no real discrepancy. Although 25% of people have salient nonbelieved memories when you interview them systematically about them, the accessibility rate to nonbelieved memories in daily retrospection might be quite low (3-6%), and understandably so: why bother about something that you do not believe. Indeed, an interesting question is: how do nonbelieved memories affect people’s attitudes and behaviour? For instance, will nonbelieved memories of sexual abuse influence retractors’ attitudes toward the family members that they previously accused of the abuse? Or will their vivid nonbelieved memories hinder the attempts of retractors to restore their relationship with their families? In order to address these questions, researchers have developed ways to experimentally evoke nonbelieved memories in the laboratory.

Not Believing a Hot Air Balloon Experience

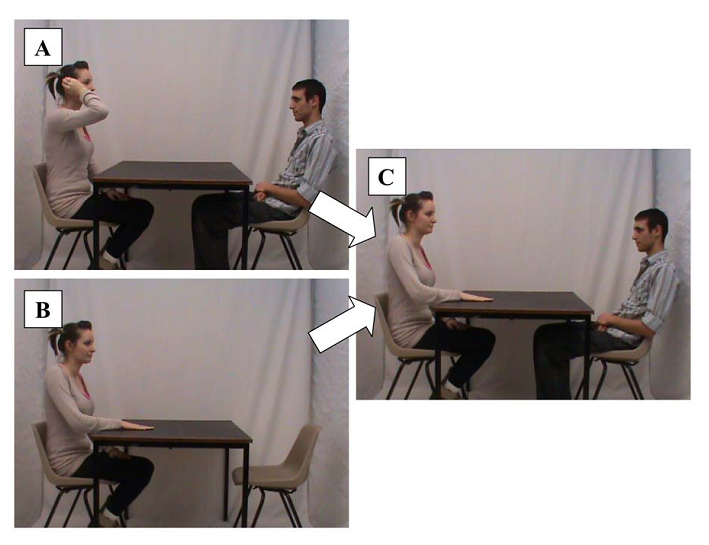

Besides studying naturally occurring nonbelieved memories, researchers have examined whether nonbelieved memories can be elicited in the laboratory. Although a plethora of research has revealed that repeatedly suggesting that a false event occurred increases confidence, belief, and even recollection for that event (Koehler, 1991), our knowledge about how to undermine belief is still quite limited. In one demonstration, Clark, Nash, Fincham and Mazzoni (2012) provided participants with fake videos (i.e., doctored-video paradigm; Nash, Wade, & Lindsay, 2009) to create nonbelieved memories. Participants were first asked to perform some actions such as clapping their hands and rubbing the table while their actions were being video recorded. Two days later, participants watched a doctored video edited by the researchers in which fake actions were embedded and in this way, participants falsely “remembered” and “believed” that they had performed the fake actions. Finally, researchers told them that actually the video clip was doctored and then measured their belief and recollection for the action. This manipulation undermined participants’ belief for 14% to 26% of the fake actions but vivid recollections for these fake actions remained.

Figure 1. Doctored video clip. (A) Real clip. (B) Fake action. (C) Doctored composite of (A) and (B). From Clark, A., Nash, R. A., Fincham, G., & Mazzoni, G. (2012). Creating non-believed memories for recent autobiographical events. PLoS ONE, 7(3): e32998. Copyright 2012 by Andrew Clark. Reprinted with permission.

In another demonstration, Otgaar, Scoboria, and Smeets (2013) used a false memory implantation procedure to experimentally elicit nonbelieved memories in children and adults. The false memory implantation method is known as an effective manipulation to create vivid mental representations for suggested false events in both children and adults (see Otgaar, Verschuere, Meijer, & Van Oorsouw, 2012). In this paradigm, individuals were: (1) provided with the narrative of a fictitious event such as a hot balloon ride when they were children; (2) guided by the experimenter to mentally “travel” back to the suggested event and think about or imagine the details of that experience; and (3) asked whether they had formed a memory for the false event across multiple interviews. Typically about 30-40% of individuals will report strong memories and beliefs for the suggested false events (Wade, Garry, Read, & Lindsay, 2002).

Otgaar and colleagues (2013) adapted this implantation method to elicit nonbelieved memories by debriefing individuals that the event suggested did not happen and then asking them whether they still believed or recollected the event. They found that for 40% of the participants who formed false memories, belief for the false event decreased, but that their memory representations for the hot balloon ride remained vivid.

Not only can people be led to form nonbelieved memories for false events, but they can also be induced to stop believing in memories for true experiences. Mazzoni, Clark, and Nash (2014) used the same procedure—the doctored video paradigm—to examine whether it was possible to persuade people to disbelieve, but recollect events that actually did happen. This topic is worth investigating because there are important real life equivalents. Consider the child victim who is told by the perpetrator that the abuse did not happen, or witnesses who are told during interrogations that genuine experiences did not occur. It is unclear how people’s memories and beliefs will be altered in such cases. Mazzoni and colleagues found that it was possible to undermine autobiographical belief for genuinely performed actions.

What Are the Implications?

Egg Salad

Recent work on the behavioural consequences of false memories has shown that false beliefs rather than false memories per se impact behaviour. Typically, participants in this type of study complete a food history questionnaire and then are told that based on their answers, the computer has generated a health profile for them. The profile falsely suggests that as a child, they had gotten ill after eating a particular food, such as egg-salad. After about two weeks, their eating behaviour is measured. People receiving the suggestion consumed significantly less egg-salad compared to the control group, and this effect can last for months (Bernstein & Loftus, 2009; Scoboria, Mazzoni, Jarry, & Bernstein, 2012). Recent work has revealed that behavioural change is solely determined by belief and not recollection (Bernstein, Scoboria, & Arnold, 2015). One interesting research enterprise is therefore to run an “egg-salad” study, but this time debrief people about the fact that the profile is false and their memories of having gotten ill from egg salad were wrong. What would be the impact of nonbelieved memories on food-related behaviour? Based on recent work (Bernstein et al., 2015), the expectation would be that people will not avoid egg salad even when still retaining the false images of being ill as a child.

Trauma

Nonbelieved memories also have the potential to illuminate the links between recollection, belief and symptoms in certain populations, such as people with a traumatic history (e.g. retractors of abusive memories, PTSD patients). A factor worth noting for why people undermine their beliefs in the occurrence of traumatic experiences is that they have a strong desire to not remember the event. In Scoboria et al.’s (2015) research, a small percentage of college respondents (4%) were uncomfortable with or disliked the content of their memories and tried to “push it away from my mind” or “did not want to believe that that happened” (p.554). They successfully compelled themselves to withdraw belief, and thus formed nonbelieved memories.

Intriguingly, people who have experienced traumatic events frequently encounter involuntary, intrusive memories of those events (Berntsen, 2010) and often adopt the strategy of denying or undermining their belief in the occurrence of traumatic events (Horowitz, 1986). If undermining belief undermines rates of memory intrusions as well, developing methods to elicit nonbelieved memories would be a meaningful research direction with practical significance. Conversely, if recollection of traumatic events impacts people’s behavioural reactions, not belief, then a logical empirical attempt would be that by deflating the genuineness of PTSD patients’ recollections, PTSD symptoms such as traumatic intrusions would decrease. But of course, it would touch upon a range of ethical issues: are therapists allowed to manipulate the content and belief-status of trauma memories?

Eyewitnesses

The criminal justice system relies heavily on eyewitness testimony. Since 1989, there have been thousands of cases where prime suspects were identified and pursued, until DNA testing proved that they were wrongly accused. 72% of these DNA exoneration cases in the US based Innocence Project were victims of mistaken eyewitness identification or false memory (http://www.innocenceproject.org/causes-wrongful-conviction). Among legal professionals, it is assumed that eyewitnesses testify and make identifications based on their “recollections”. Yet, we know that in eyewitnesses too, belief and recollection sometimes are confounded as it is unknown whether eyewitnesses make identifications based on their false beliefs or false memories or both.

There are reasons to believe that belief in the occurrence of an event also plays a part in eyewitness testimony. Memory researchers have often failed to distinguish between memory and belief (Scoboria et al., 2004). Can witnesses discriminate between their memories and the beliefs for the occurrence of their recollections? If eyewitnesses are educated with the distinction between memory and belief, will it lower misidentification rate?

Research on nonbelieved memories may shed light on how witnesses’ reports may be altered under certain circumstances. For instance, information from one witness could be indirectly passed to another witness through a third party, such as a police officer, who informs the witness about what another witness had said (Luus & Wells, 1994). When the information provided by the police officer contradicts with the witness’s memory, the witness may undermine his belief in his memory and choose to not report certain details. What we need is research on this type of dynamic; how social feedback leads to nonbelieved memories and further influences behavioural output in the legal area.

To conclude, a novel line of research has emerged showing that recollection and belief are distinct constructs sometimes ending up in the creation of nonbelieved memories. Nonbelieved memories have been considered to be a rare and exceptional phenomenon, but this review shows that they can easily be elicited in an experimental setting. The next step is to examine how nonbelieved memories affect our behaviour and whether our belief, recollection, or both determine the way we behave and act. This line of study has important implications for law, therapy and much else.

References

Bernstein, D. M., & Loftus, E. F. (2009). The consequences of false memories for food preferences and choices. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 135–139.

Bernstein, D. M., Scoboria, A., & Arnold, R. (2015). The consequences of suggesting false childhood food events. Acta Psychologica, 156, 1–7.

Berntsen, D. (2010). The unbidden past: Involuntary auto-biographical memories as a basic mode of remembering. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19, 138–142.

Brewer, W. F. (1996). What is recollective memory? In D. C. Rubin (Ed.), Remembering our past: Studies in autobiographical memory (pp. 19-66). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Clark, A., Nash, R. A., Fincham, G., & Mazzoni, G. (2012). Creating non-believed memories for recent autobiographical events. PLoS ONE, 7(3): e32998. Retrieved from http://www .plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal .pone.0032998.

Horowitz, M. (1986). Stress-response syndromes: a review of post-traumatic and adjustment disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 37, 241-249.

Howe, M. L., & Knott, L. M. (in press). The fallibility of memory in judicial processes: Lessons from the past and their modern consequences. Memory.

James, W. (1890/1950). The principles of psychology (Vol. I). New York: Dover.

Kassin, S. M., & Gudjonsson, G. H. (2004). The psychology of confession evidence: A review of the literature and issues. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 35–69.

Koehler, D. J. (1991). Explanation, imagination, and confidence in judgment. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 499-519.

Lambert, K., & Lilienfeld, S. (2007). Brain stains. Scientific American Mind, 18, 46–53.

Lipton, A. (1999). Recovered memories in the courts. In S. Taub (Ed.), Recovered memories of child sexual abuse: Psychological, social, and legal perspectives on a contemporary mental health controversy (pp. 165–210). Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

Loftus, E. F. (1993). The reality of repressed memories. American Psychologist, 48, 518-537

Loftus, E. F. (2005). Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory. Learning and Memory, 12, 361–366.

Luus, C. A. E., & Wells, G. L. (1994). The malleability of eyewitness confidence: Co-witness and perseverance effects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 714–723.

Mazzoni, G. A. L., Clark, A., & Nash, R. A. (2014). Disowned recollections: Denying true experiences undermines belief in occurrence but not judgments of remembering. Acta Psychologica, 145, 139–146.

Mazzoni, G. A. L., Scoboria, A., & Harvey, L. (2010). Nonbelieved memories. Psychological Science, 21, 1334–1340.

Nash, R. A., Wade, K. A., & Lindsay, D. S. (2009). Digitally manipulating memory: Effects of doctored videos and imagination in distorting beliefs and memories. Memory &Cognition, 37, 414–424.

Ost, J., Costall, A., & Bull, R. (2002). A perfect symmetry? A study of retractors’ experiences of making and then repudiating claims of early sexual abuse. Psychology, Crime & Law, 8, 155–181.

Otgaar, H., Scoboria, A., & Mazzoni, G. (2014). On the existence and implications of nonbelieved memories. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 349–354.

Otgaar, H., Scoboria, A., & Smeets, T. (2013). Experimentally evoking nonbelieved memories for childhood events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39, 717–730.

Otgaar, H., Verschuere, B., Meijer, E. H., & van Oorsouw, K. (2012). The origin of children’s implanted false memories: Memory traces or compliance. Acta Psychologica, 139, 397–403.

Patihis, L., Ho, L. Y., Tingen, I. W., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Loftus, E. F. (2014). Are the “memory wars” over? A scientist-practitioner gap in beliefs about repressed memory. Psychological Science, 25, 519–530.

Piaget, J. (1951). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood (L. Gattegno & F.M. Hodsen, Trans.). New York: Norton.

Sagana, A., Sauerland, M., & Merckelbach, H. (2012). It’s your choice! – Or is it really? The Inquisitive Mind, Issue 14. Retrieved from http://www.in-mind.org/article/its-your-choice-or-is-it-really.

Scoboria, A., Boucher, C., & Mazzoni, G. (2015). Reasons for withdrawing belief in vivid autobiographical memories. Memory, 23, 545–562.

Scoboria, A., Mazzoni, G., Jarry, J. L., & Bernstein, D. M. (2012). Personalized and not general suggestion produces false autobiographical memories and suggestion-consistent behavior. Acta Psychologica, 139, 225–232.

Scoboria, A., Mazzoni, G., Kirsch, I., & Relyea, M. (2004). Plausibility and belief in autobiographical memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 791–807.

Scoboria, A., & Talarico, J. M. (2013). Indirect cueing elicits distinct types of autobiographical event representations. Consciousness and Cognition, 22, 1495–1509.

Wade, K. A., Garry, M., Read, J. D., & Lindsay, S. (2002). A picture is worth a thousand lies: Using false photographs to create false childhood memories. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9, 597–603.

![US courtroom - Carol M. Highsmith [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons US courtroom - Carol M. Highsmith [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/d9_middle_500_/public/field/image/courtroom_united_states_courthouse_davenport_iowa.jpg?itok=jmoDyMV1)