Peter was a student in his early twenties, and apart from several inconsequential trysts, had spent most of his life alone and indifferent to the world of love and romance. He had, in fact, become so accustomed to this lifestyle that he assumed this would be his fate, and had made peace with the prospects of a cold and lonely existence. This assumption was proven wrong when Peter met Gwen, a girl Peter had chanced to meet in one of his elective courses. Gwen aroused in Peter feelings that he had never experienced before, and he found himself uncharacteristically smitten.

The feelings were immediately mutual, and within days of meeting Peter and Gwen were spending every available minute together, sharing a deep and committed relationship based on trust, passion, and intense warm feelings. Peter found his isolated existence a thing of the past, replaced now with heart-felt intimacy he had thought reserved for romance novels. Blinded by the glow of their love, Peter was almost devastated when Gwen revealed to him that she had slept with his best friend, Harry. She had fallen for Harry now, discarding Peter as if he were an inanimate object. The warmth that Peter once felt for Gwen was instantly extinguished, replaced by the cold shivers of betrayal and loneliness. The devastation that Peter experienced not only returned him to his once chilly and distant self, but also plunged him even further into new depths of coldness.

You yourself might have experienced the same type of overwhelming commitment Peter felt at one time in his life. Conversely, you may at one time have experienced a similar type of betrayal or rejection. Were such feelings accompanied by an immense sense of warmth, or a surge of coldness sweeping over your body? In our story, we related Peter’s experiences through linguistic conveniences called metaphors, many of which were expressed in terms of temperature: Warmth when describing affection and psychological closeness, and coldness when describing loneliness and psychological pain. Metaphors that describe physical experiences, like physical warmth, often reflect very meaningful personal experiences, such as social rejection or interpersonal intimacy. But how do we come to express ourselves in such metaphors?

In the last decade, social psychology (amongst other disciplines) has focused on how the body may influence how people behave, think, and feel. This seems like a very novel idea – unfortunately it isn’t. One of the fathers of modern psychology, William James (1884), had already proposed that without their bodily components, emotions are essentially non-existent. Though James' claim may have been a bit over the top, his line of reasoning was an important step towards recognizing links between mind and body.

Some of these principles might seem obvious, such as the finding that the expression of a smile can influence how you really feel. Or, that the way you stand influences your attitude on a position (see Briñol, 2009). But how would this work in terms of more complex ideas, like the way you feel about other people? As it turns out, even people who are not professional psychologists posses pretty good intuitions about the relationship between body and mind. We are simply raised with these ideas – perhaps even outside of our conscious awareness. The way we move, the way we learn how to gesture, and even through the way we speak we learn complex body-mind interactions.

The study of language has been instrumental in identifying and discussing body-mind links. Linguists Lakoff and Johnson (1980, 1999) in particular have been very influential in elaborating upon these ideas. Simply put, they proposed that people utilize very concrete experiences to understand more complex ideas. The chills, or that warm and fuzzy feeling, may indeed affect the way we feel about others. In order to understand the role of warmth on our relationships, we have put together a research program to investigate the role of physical warmth in people’s social cognition.

Thoughts, metaphors, and feelings

Psychology has now amassed an enormous literature on how people think. As a very brief summary of some decades of research, we can conclude that people make use of schemas, which contain the properties about specific experiences in memory. Schemas are mental representations, which represent some aspect of the world. For example, you may have built a schema in your mind about the elderly, which are often characterized as needing help, slow-moving, and so forth (we often refer to these schemas as stereotypes). Social psychologists have been very successful in activating the properties of schemas (this process is called priming). For example, John Bargh and his colleagues (1996) primed students with the stereotype of elderly (through words like Florida, old, lonely, et cetera), which in turn caused the students to walk slower (though this effect did not replicate with psychology students in Belgium, see Doyen, Klein, Pichon, & Cleeremans, 2010).

Now what does this have to do with the metaphor story? Psychologist Mark Landau and his colleagues (2010) recently proposed that we can analyze people’s conceptual thoughts by examining the properties of two different schemas in order to understand much more complex concepts, through a process called metaphoric transfer strategy. Through this strategy, we can come to understand how people combine different schemas through so-called conceptual metaphors (see Lakoff & Johnson, 1999). Conceptual metaphors combine the physical experiences of one concept with the more abstract properties of another concept. For instance, the expression “Friday is far away” may seem natural, but actually reflects the use of a spatial description (distance) for a temporal property (the time until Friday). Thus, in order to understand some very complex ideas about time, we recruit the more intuitive concept of space (see Boroditsky & Ramscar, 2002, and Casasanto & Boroditsky, 2008, for more information on this idea).

Your mother, metaphor, and other matters

But why might people build up such associations? In building the case for conceptual metaphors, Lakoff and Johnson (1999) discuss the idea of primary metaphors. Because people may jointly express concepts like time and space in metaphors (e.g., like the earlier mentioned Friday being far away), they may acquire a very basic association between related concepts that one acquires early and often. Furthermore, such associations come to exist between abstract concepts (such as social phenomena) and more concrete experience (such as physiological states).

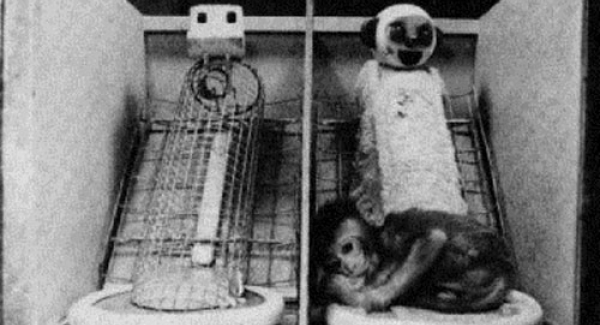

Let us now return to the subject of interpersonal warmth. Time and space are not the only concepts you experience jointly; the world is rich with examples of metaphoric transfer. The primary focus of our research has been on the relationship between physical warmth and feelings of affection. From the moment of your birth, you have experienced feelings of affection and physical warmth jointly – most likely beginning when your mother used to hold you. This is a very basic body-mind connection that has been recognized by many social psychologists.

Because social connections are so fundamentally important to people, social psychologists have proposed that interpersonal warmth is the most important dimension on how we judge people (Asch, 1946; Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, 2007). It is thus only natural that interpersonal warmth has been the focus of research investigating metaphoric structuring. A couple of years ago, Lawrence Williams and John Bargh (2008) wanted to test the link between physical and psychological warmth. In keeping with the hypothesized link between psychological and physiological warmth, people that had just held a cup of warm coffee (versus a cup of iced coffee) judged a third person as more sociable and more affectionate – entirely indicative of a warm personality! In a follow-up study, Williams and Bargh even found that people became more generous after having a warm gel pack placed on their neck. And indeed, these effects reflect something about how we learn relationships: Young children show similar effects, but only if they are securely attached (IJzerman, Karremans, Thomsen, & Schubert, in press). These ideas have been elaborated on since – but may go beyond conceptual metaphors.

Our Thoughts: Just Monkey Business?

In recent years, we have conducted a number of studies to test how physical warmth may influence people’s psyche. Our findings indicate that in addition to affecting judgements of others and generosity, physical warmth is associated with a broader array of effects. When we put our participants in a warm room, they judged the experimenter they had just interacted with as being psychologically closer. We tested this through a pictorial scale, in which one circle represents the participant and the other the experimenter – through an oft-used measurement in research on relationships (see e.g., Aron, Aron, & Smollan, 1991; Gunz, 2008; and the illustration below).

In addition to this, we even found that a warm room also lead to participants using more verbs (as compared to adjectives; Peter kisses Gwen, for example, illustrates their relationships, whereas Peter is a loving partner does not) and adopting a relational perceptual focus (seeing the relationship between objects, rather than the properties; for an example, see the figure below, choice A). The findings from these studies provide strong support that physiological states are linked to social concepts.

Physical Warmth: More than Just a Metaphor

Psychologists (and other scientists) have accumulated a vast array of theory and research that the body plays a significant role in behavior and thought. But, this link is not easy and straightforward. It is tempting to rely on linguistic expressions or basic observations in order to understand how we think and feel. Metaphors may link different concepts and thus give us an enormous amount of information, but metaphors may also merely reflect very basic human experience.When we make people feel more similar, they estimate the room temperature as higher. When we socially exclude them, their skin temperature drops. And, holding a physically warm cup really makes you feel better if you have been rejected. Physical warmth is thus more than just a metaphor; the connection between loving feelings and physical warmth reflects an experience on which we (arguably) rely from birth on in order to know who to trust or who not to trust. These findings indicate strongly that conceptual metaphors extend beyond structures such as time and space, and into more experiential domains, such as interpersonal warmth.So what does this large body of information show us? The recurring theme of this paper has been that thoughts and concepts do not just exist as disembodied ideas, disconnected and separated from our bodies. Instead, the evidence points to a reality in which our physiological states are very much a determinant of, and reaction to, social phenomena. Just as our bodies can influence how we feel about interpersonal situations, so too can interpersonal situations bring about shifts in our bodily states. It is thus obvious that the mind and body are not divorced as was once popular opinion in the social sciences, but instead inextricably linked in such a way that we are able to better experience and understand our social worlds.The way you engage in interaction with others are fundamentally shaped by early mind-body connections. The way one attaches to others are not simply shaped by our thoughts or the concepts from software to hardware. The mannerisms of our hardware are so fundamental to the way we think and feel about others, that the way of the body may change the way we learn to know our world. Thus, in the scenario described in the beginning, Peter might have literally experienced the type of coldness often thought to be reserved for metaphor; a physical response to the depth in which his social world plunged him. However, all is not necessarily lost for our protagonist: The effect is not unidirectional and the simulations described in this paper could similarly work to imbue him with the warmth of new, less damaging, romantic relationships.

References

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., Tudor, M., & Nelson, G. (1991). Close relationships as including other in the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 241-253.

Asch, S. E. (1946). Forming impressions of personality. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 41, 258 – 290.

Bargh, J. A., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 230-244.

Bargh, J. A. & Shalev, I. (2011). The substitutability of physical and social warmth in daily life. In press at Emotion.

Barsalou, L. W. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22, 577 – 560.

Boroditsky, L., & Ramscar, M. (2002). The roles of body and mind in abstract thought. Psychological Science, 13, 185-189.

Briñol, P. (2009). Embodied persuasion: How the body can change our mind. InMind.org, 9. Retrieved from http://beta.in-mind.org/node/312

Caporael, L. R. (1997). The evolution of truly social cognition: The core configurations model. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 1, 276 – 298.

Casasanto, D., & Boroditsky, L. (2008). Time in the mind: Using space to think about time. Cognition, 106, 579 – 593.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Science, 11, 77 – 83.

Gunz, A. (2008). The anatomy of love. InMind.org, 7. Retrieved from http://beta.in-mind.org/node/206

Harlow, H. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13, 673 – 685.

IJzerman, H., Gallucci, M., Pouw, W. T. J. L., Weissgerber, S. C., Van Doesum, N. J., Vetrova, M., & Williams, K. D. (2012). Cold-blooded loneliness: Social exclusion leads to lower skin temperatures. Acta Psychologica.

IJzerman, H., & Koole, S. L. (2011). From perceptual rags to metaphoric riches: Bodily, social, and cultural constraints on sociocognitive metaphors. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 355 – 361.

IJzerman, H., & Semin, G. R. (2009). The thermometer of social relations: Mapping social proximity on temperature.Psychological Science, 10, 1214 – 1220.

IJzerman, H. & Semin, G. R. (2010). Temperature as a ground for social proximity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 867 – 873.

James, W. (1884). What is an emotion? Mind, 9, 188 – 205.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Landau, M. J., Meier, B. P., & Keefer, L. A. (2010). A metaphor-enriched social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 163, 1045-1067.

Williams, L. E., & Bargh, J. A. (2008). Experiencing physical warmth promotes interpersonal warmth. Science, 322, 606-607.

Williams, K. D., & Jarvis, B. (2006). Cyberball: A program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance.Behavior Research Methods, 38, 174-180.

Zhong, C., & Leonardelli, G. J. (2008). Cold and lonely: Does social exclusion feel literally cold? Psychological Science, 19,838-842.