Recent research in social psychology has demonstrated that the facial appearance of Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) and other business leaders predicts their companies’ financial performance. In this article, we review initial evidence illustrating the relation between CEO facial appearance and corporate success. We then delve into more recent research on how this relationship varies by economic climate, leader ethnicity, and CEO sex. Further studies are discussed that examined how facial cues related to CEO success vary across cultures. Finally, we discuss the implications of this research, and how these findings relate to real world organizations.

---

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but does this apply to pictures of peoples’ faces? People can obviously determine traits like race, sex, and age from a look at the face. New research in the field of perceptual psychology, however, has shown that one can judge less obvious aspects of someone’s personality, too. Dimensions such as religious beliefs (Rule, Garrett, & Ambady, 2010), political affiliation (Samochowiec, Wanke, & Fiedler, 2010), and sexual orientation (Rule, Ambady, Adams, & Macrae, 2008) can all be judged more accurately than chance guessing from looking at faces. Recently, this line of investigation has shown that people can judge another kind of trait from faces, one that has interesting implications for business and human resources: business leadership ability. That is, people can roughly tell how good of a leader someone is just from looking at his or her face.

Facial appearance and CEO success – the first studies

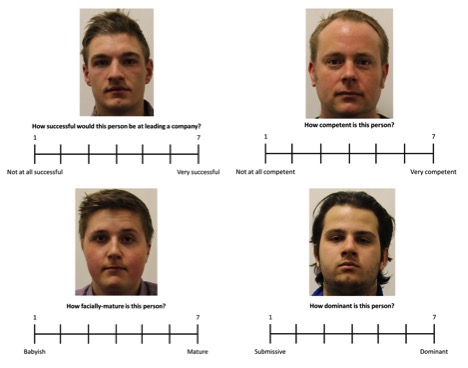

There is a long history of research demonstrating that facial appearance influences leadership selection in politics (see Olivola & Todorov, 2010, for review). More recently, however, an expanding literature in psychology and management has shown that facial appearance predicts the present or future financial success of business leaders. The first such study in this field was simple enough: undergraduate students viewed photos of 50 CEOs from the Fortune 1000 (Rule & Ambady, 2008). Participants were given headshot portraits of the CEOs (none of them recognized the CEOs, in fact they did not know the people in the photos were CEOs) and were asked to rate them for leadership ability (Figure 1). Separate participants rated the faces for emotional affect and attractiveness and CEO age was calculated to control for these extraneous variables when the researchers measured the relationship between perceived leadership ability and the companies’ actual profits. The results showed that facial appearance predicted the CEOs’ ability to successfully lead their companies, as indicated by the amount of profit that each CEO’s company had publicly reported earning. A second experiment found that how competent, dominant, and mature each CEO seemed from their image explained the relationship between facial appearance and firm performance (Rule & Ambady, 2008). These trait perceptions are often associated with masculine facial characteristics (e.g., Watkins, 2011). The results of these studies were astonishing: naïve judgments of leadership success from business leaders’ faces predicted how successful they were in leading their company to financial gain.

Is your face your fate? Why leaders look like leaders

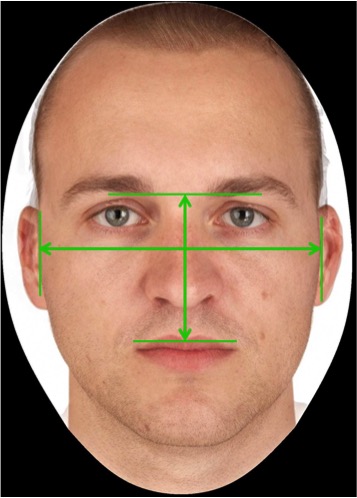

The hiring and selection of business CEOs can be a fickle process with plenty of lateral movement across companies (Brickley, 2003). This is substantially less frequent in law firms, however. All law firm managing partners (MPs; the analogue to a company’s CEO) must have completed law school, done well enough to get hired at a firm, made partner at that firm, and then ascended the ranks to become its leader (Galanter & Palay, 1991). This is a steep ladder to success that typically cannot be assisted by one’s name or family connections (as may be the case with CEOs of Fortune 1000 companies, such as the Ford dynasty). It is a safe assumption that the leaders of America’s top law firms are an elite group of highly competent individuals. Yet, just as with the Fortune 1000 CEOs, people can also predict the profitability of law firms from the faces of their MPs (Rule & Ambady, 2011a). More striking, MP’s current facial appearance not only predicted the recent success of the US’s top 100 law firms, but photos of the MPs from their undergraduate yearbooks predict their firms’ current success just as well (Rule & Ambady, 2011b). This is remarkable, as college yearbook photos would have been taken before the MPs even entered law school, possibly before they even applied. This suggests that there is something static and stable about facial appearance that leads to these relationships. Such relationships could even be biologically-based. For example, the same hormones that shape the development of a person’s face are also involved in the development of some aspects of personality (Fink et al., 2005; Fink, Manning, & Neave, 2004). Thus, the same biochemical process that makes someone look like a leader may also give him or her the personality to become one. Indeed, one study has shown that facial width-to-height ratio (fWHR), a physical facial measurement associated with testosterone in men (Lefevre, Lewis, Perrett, & Penke, 2013), predicts company profit when measured in the faces of CEOs of successful large-scale businesses with simple leadership hierarchies (that is, where the CEO yields a great deal of firm decision-making power; Wong, Ormiston, & Haselhuhn, 2011); see Figure 2.

One possibility that arises from this reasoning is that more successful companies may hire more “successful-looking” CEOs. One unpublished study found that judgments of CEO competence do not correlate with companies’ return-on-assets (ROA) after controlling for several related variables, including the company’s ROA under the previous CEO (Graham, Harvey, & Puri, 2015). Other studies, however, have found that CEOs’ facial shape predicts their companies’ ROA when controlling for the organization’s ROA before they were hired (Wong, Haselhuhn, & Ormiston, 2011), and that ratings of leadership from CEOs’ faces predict their companies’ profits when controlling for the profits of their predecessors and successors (Re & Rule, 2015). These studies suggest that, although more successful firms may hire successful-looking leaders, there seems to be a kernel of truth in the leader-like appearance of prosperous CEOs.

Context counts – moderators in facial appearance and leadership

Economic climate. There are conditions that moderate the relationship between facial appearance and CEO success. For example, the global recession of the late 2000s had deleterious effects on the economies of most nations in the world, which took years to recover (Imbs, 2010; Verick & Islam, 2010). One study demonstrated that judgments of leadership and personality traits of American CEOs’ faces could predict company profits in the fiscal years leading up to the recession (2005-2008), but not in the years immediately following it (2009-2011; Rule & Tskhay, 2014). This suggests that the facial characteristics associated with CEO success may have changed after the financial collapse in the U.S., when executive strategies were likely radically altered (Williamson & Zeng, 2009).

To confirm that this change was related to the economic crisis, the researchers conducted a second study to see whether facial traits still related to CEO success following the crisis in a country that was relatively unscathed by the recession: Germany. Germany endured the economic crisis much more successfully than other Western nations, and the German economy recovered at a much faster rate (Burda & Hunt, 2011). Interestingly, judgments of the personality traits that correlated with American CEO success before the financial crisis predicted German CEO success after the financial crisis (Rule & Tskhay, 2014). The relationship between judgments of faces and CEO success in U.S. companies therefore seems to have been weakened by the unstable economic climate of the late 2000s. In all, these studies suggest that the relationship between facial appearance and CEO success is moderated by economic context, and disrupted by harsh financial climates.

CEO Ethnicity. Another moderator of facial appearance and CEO success is ethnicity. Inter-group image theory suggests that Black individuals evoke greater feelings of threat than other groups (Alexander, Brewer, & Hermann, 1999; Alexander, Brewer, & Livingston, 2005). As a result of these widely-held but overgeneralized and often erroneous stereotypes of Black people, a dominant and powerful appearance in the face of a Black person may exacerbate the perceived level of threat and be disadvantageous to Black individuals in corporate roles. Conversely, a “baby-faced” appearance, which attenuates perceptions of dominance and threat (Zebrowitz, 1997), may minimize feelings of threat and competition. Black individuals with babyfaces may therefore benefit in mixed-ethnicity workplaces (such as the American business landscape) because the stereotypes about babyfaced people may partially combat the stereotypes about Black people. One pair of researchers tested this empirically (Livingston & Pearce, 2009). They found that Black male CEOs (either current or former CEOs of companies ranked on the Fortune 500 listing) were rated as more baby-faced than White CEOs, even though a separate sample revealed that Black people were perceived as less baby-faced than White people in the general population. Moreover, babyfacedness positively associated with Black CEOs’ individual financial compensation, as well as their company’s status in the Fortune 500, though these correlations did not reach statistical significance due to the small number of Black CEOs in the sample (faces of only 10 Black CEOs could be collected for stimuli). These results suggest that, although a baby-faced appearance can have deleterious effects for White leaders who may strive to look dominant and powerful (Zebrowitz & Montepare, 2005), it may reduce perceptions of threat so as to benefit Black CEOs in corporate America.

What about the women?

Most CEOs of successful large-scale corporations are men (Oakley, 2000). This leaves open the question of whether the faces of female leaders might also provide clues to their success, particularly as the traits predicting success tend to be associated with masculinity (e.g., dominance; Riggio & Riggio, 2010). To address this, one study gathered the faces of all 20 female CEOs in the Fortune 1000:2006 list (all but one of whom was Caucasian), and found that judgments of competence and leadership ability predicted company profit when controlling for their ages, emotional affect, and attractiveness (as in the preceding study with male CEOs; Rule & Ambady, 2008), as well as perceptions of their masculinity (which alters perceptions of female leaders; Sczesny, Spreeman, & Stahlberg, 2006). Despite the difference in sex, these judgments are similar to those that predict profit for male CEOs (Rule & Ambady, 2008), demonstrating that facial appearance is a reliable predictor of CEO success among both men and women.

A recent study probed the question of female CEOs further by matching 20 female CEOs from the Fortune 1000:2007 listing with 20 male CEOs of companies ranked directly above or below them (Pillemer, Graham, & Burke, 2014). The results of this study found that judgments of powerfulness predicted the profits for companies led by male CEOs (as in the earlier work), but that judgments of compassion and supportiveness actually predicted the success of female CEOs. Furthermore, a composite of judgments of communal traits (compassion, interpersonal warmth, supportiveness) predicted company rank and profit when controlling for the female CEOs’ ages, affect, and attractiveness. These findings suggest that the relationship between facial appearance and leader success for female CEOs may be moderated by traits more traditionally ascribed to women, a contextual factor comparable to those found for culture and ethnicity. Interestingly, a composite of agentic traits (competence, dominance, facial maturity, leadership, powerfulness) marginally correlated with company rank as well, a finding that the researchers interpreted as supporting the theory that perceptions of leadership may be becoming more androgynous in the modern era (Koenig et al., 2011). Although this may be true, both studies examining female CEOs were limited by the small sample of women available in the Fortune 1000 listings. It is clear, however, that leadership success can be foretold by facial appearance of women as well as men. It will be exciting for future research to elucidate how a leader’s sex interacts with the facial traits that correlate with leadership success.

Lost in translation: Leadership appearance across cultures

Several studies have demonstrated a link between facial appearance and CEO success in Western businesses (e.g., Livingston & Pearce, 2009; Rule & Ambady, 2008, 2009). The relationship between facial appearance and CEO success is not universal, however. Indeed, the same facial traits that predict the success of CEOs of Western companies are not related to financial performance for the CEOs of top-ranking Japanese (Rule, Ishii, & Ambady, 2011) or Chinese (Harms, Han, & Chen, 2012) companies. Studies have demonstrated that American and Japanese perceivers agree in the personality inferences that they make about both American and Japanese male politicians (Rule et al., 2010). Importantly, though, different traits predict who wins the elections in each culture. Specifically, traits related to warmth predict the electoral success of Japanese politicians whereas traits related to power predict the outcomes of American elections. Likewise, Americans (who value power in leaders) can reliably prognosticate which candidates will win US elections and Japanese (who value warmth in leaders) can do so for elections in Japan, but neither group can effectively forecast who will win elections in the other nation because they apply their own set of values (e.g., Americans assume that Japanese voters will elect powerful leaders the way that they do). Thus, although people from different cultures may agree in their perceptions of traits from faces, they use this information very differently when forming impressions of leadership because they rely on the values inherent to their own culture.

Similar to politicians, the discrepancies in facial traits that correlate with the success of CEOs in Eastern and Western nations are not due to differences in perceptions of personality. Instead, they are likely due to differences in leadership styles (Den Hartog et al., 2000; Jung & Avolio, 1999). In the West, leaders are traditionally ascribed domineering, powerful traits (more closely related to “transactional” leadership; Bass, 1985; Burns, 1978). Accordingly, the most successful CEOs in the West look powerful (Rule & Ambady, 2008; Rule & Tskhay, 2014). Conversely, leaders in the East are typically perceived as more collectivist and persuade followers to work towards the group goal (more closely tied to a “transformational” leadership style; Jung & Avolio, 1999). It is therefore not surprising that perceptions of dominance and power do not relate to CEO success in China and Japan (Harms et al., 2012; Rule et al., 2011). The facial cues to CEO success are therefore not universal. Rather, they seem to be modified by cultural norms. Indeed, research has found that financial performance of Chinese CEOs related to perceptions of risk-taking proclivity (Harms et al., 2012), a personality trait that may be uniquely suited to the success of leaders in China because of the uncertain and dynamic nature of Chinese corporate culture (Chang, 2009).

Facing the facts: What people should do with this

These topics clearly warrant additional exploration, and such research is actively underway. As new research is published, however, an emerging theme is becoming clear: facial appearance is related to success in business. Indeed, estimates suggest that business leaders’ facial appearance predicts up to 14% of the difference in profits between different companies (Rule & Ambady, 2008, 2011a). So what are people to make of these findings?

The temptation for cosmetic surgery notwithstanding, facial appearance might play a role only as a measure of last resort. Among a highly qualified pool of candidates, the evaluation of abilities may reach a ceiling at which it becomes difficult to distinguish one candidate from another. In these cases, candidate selection could fall to a qualitative judgment: a gut feeling about who might be best. These intangible assessments may be the exact province of facial appearance. The person who best looks the part may inch ahead among a pool of excellent leaders. It has long been known that physically attractive people are thought to have more positive traits than less attractive people (Dion, Berscheid & Walster, 1972), and studies in human resources have found that this bias affects how likely someone is to be hired (Dipboye, Arvey, & Terpstra, 1977). Along this line of argument, psychologists have shown that, in the absence of better information, physical traits can be used as a proxy for behavior. Over the span of a career, these effects could accumulate so that the individual chosen to lead gets more experience with leadership, might receive sponsorship to attend seminars on leadership, and may be given the opportunity to learn and refine the skills needed to succeed as a leader. All this leads to more success. In short, people can become leaders simply because they look like leaders.

Yet a word of caution is also warranted. The face may serve as a proxy for talent but it is scarcely its replacement. Accuracy in judging behavior and psychological traits from faces appears to be specific to certain domains. Whereas some judgments are accurate (e.g., personality is reliably judged from facial cues; Ambady, Hallahan, & Rosenthal, 1995; Berry, 1990), others are surprisingly inaccurate (e.g., people rely on their gut feelings about others’ honesty but can be notoriously inaccurate, as in the case of Bernie Madoff’s investors; see Rule, Krendl, Ivcevic, & Ambady, 2013). Impressive as the predictive validity of facial appearance can be, many—possibly most—domains of life do not manifest themselves in perceptible facial cues. Leadership among top executives, however, does appear to be one exception to this. The face may convey useful information about an individual’s leadership potential and appear to outperform more rational or objective measures of success. Whether this is because the face is a sort of “Trojan Horse” of hidden traits and talents, or because particular facial features entrain other people to follow an individual, there is something subtle in the face that communicates a leader’s success.

References

Alexander, M. G., Brewer, M. B., & Hermann, R. K. (1999). Images and affect: A functional analysis of out-group stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 78.

Alexander, M. G., Brewer, M. B., & Livingston, R. W. (2005). Putting stereotype content in context: Image theory and interethnic stereotypes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 781-794.

Ambady, N., Hallahan, M., & Rosenthal, R. (1995). On judging and being judged accurately in zero-acquaintance situations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 518-529.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: The Free Press.

Berry, D. S. (1990). Taking people at face value - Evidence for the kernel of truth hypothesis. Social Cognition, 8, 343-361.

Brickley, J. A. (2003). Empirical research on CEO turnover and firm-performance: A discussion. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 36, 227-233.

Burda, M. C., & Hunt, J. (2011). What explains the German labor market miracle in the Great Recession? National Bureau of Economic Research, Working paper No. 17187.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

Chang, L. T. (2009). Factory girls: From village to city in a changing China: Random House LLC.

Den Hartog, D. N., House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Ruiz-Quintanilla, S. A., & Dorfman, P. W. (1999). Culture specific and cross-culturally generalizable implicit leadership theories: Are attributes of charismatic/transformational leadership universally endorsed? The Leadership Quarterly, 10, 219-256.

Dipboye, R. L., Arvey, R. D., & Terpstra, D. E. (1977). Sex and physical attractiveness of raters and applicants as determinants of resumé evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62, 288-294.

Dion, K., Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1972). What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24, 285-290.

Fink, B., Grammer, K., Mitteroecker, P., Gunz, P., Schaefer, K., Bookstein, F. L., & Manning, J. T. (2005). Second-to-fourth digit ratio and face shape. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 272, 1995-2001.

Fink, B., Manning, J. T., & Neave, N. (2004). Second-to-fourth digit ratio and the 'big five' personality factors. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 495-503.

Galanter, M., & Palay, T. (1994). Tournament of lawyers: The transformation of the big law firm. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Graham, J. R., Harvey, C. R., & Puri, M. (unpublished manuscript). A Corporate Beauty Contest (No. w15906). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Harms, P. D., Han, G., & Chen, H. (2012). Recognizing leadership at a distance a study of leader effectiveness across cultures. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 19, 164-172.

Imbs, J. (2010). The first global recession in decades. IMF Economic Review, 58, 327-354.

Jung, D. I., & Avolio, B. J. (1999). Effects of leadership style and followers' cultural orientation on performance in group and individual task conditions. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 208-218.

Koenig, A. M., Eagly, A. H., Mitchell, A. A., & Ristikari, T. (2011). Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 616-642.

Lefevre, C. E., Lewis, G. J., Perrett, D. I., & Penke, L. (2013). Telling facial metrics: facial width is associated with testosterone levels in men. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34, 273-279.

Livingston, R. W., & Pearce, N. A. (2009). The teddy-bear effect: Does having a baby face benefit black chief executive officers? Psychological Science, 20, 1229-1236.

Oakley, J. G. (2000). Gender-based barriers to senior management positions: Understanding the scarcity of female CEOs. Journal of Business Ethics, 27, 321-334.

Olivola, C. Y., & Todorov, A. (2010). Elected in 100 milliseconds: Appearance-based trait inferences and voting. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 34, 83-110.

Pillemer, J., Graham, E. R., & Burke, D. M. (in press). The face says it all: CEOs, gender, and predicting corporate performance. In press at Leadership Quarterly, DOI: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.07.002.

Re, D.E., & Rule, N.O. (unpublished manuscript). Making a (False) Impression: The Role of Business Experience in First Impressions of CEO Leadership Ability. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Riggio, H. R., & Riggio, R. E. (2010). Appearance-based trait inferences and voting: Evolutionary roots and implications for leadership. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 34, 119-125.

Rule, N. O., & Ambady, N. (2008). The face of success - Inferences from chief executive officers' appearance predict company profits. Psychological Science, 19, 109-111.

Rule, N. O., & Ambady, N. (2009). She's got the look: Inferences from female Chief Executive Officers' faces predict their success. Sex Roles, 61, 644-652.

Rule, N. O., & Ambady, N. (2011a). Face and fortune: Inferences of personality from Managing Partners' faces predict their law firms' financial success. Leadership Quarterly, 22, 690-696.

Rule, N. O., & Ambady, N. (2011b). Judgments of power from college yearbook photos and later career success. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2, 154-158.

Rule, N. O., Ambady, N., Adams, R. B., & Macrae, C. N. (2008). Accuracy and awareness in the perception and categorization of male sexual orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1019-1028.

Rule, N. O., Garrett, J. V., & Ambady, N. (2010). On the perception of religious group membership from faces. PLoS One, 5, e14241.

Rule, N. O., Ishii, K., & Ambady, N. (2011). Cross-cultural impressions of leaders' face: Consensus and predictive validity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35, 833-841.

Rule, N. O., Krendl, A. C., Ivcevic, Z., & Ambady, N. (2013). Accuracy and consensus in judgments of trustworthiness from faces: Behavioral and neural correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 409-426.

Rule, N. O. & Tskhay, K. O. (2014). The influence of economic context on the relationship between chief executive officer facial appearance and company profits. In press at Leadership Quarterly. DOI: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.01.001.

Samochowiec, J., Wanke, M., & Fiedler, K. (2010). Political Ideology at Face Value. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1, 206-213.

Sczesny, S., Spreemann, S., & Stahlberg, D. (2006). Masculine = competent? Physical appearance and sex as sources of gender-stereotypic attributions. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 65, 15–23.

Verick, S., & Islam, I. (2010). The great recession of 2008-2009: causes, consequences and policy responses. IZA Discussion Paper No. 4934.

Watkins, C.D. (2011) Dominant themes. The Psychologist, 24, 550-551.

Williamson, P. J., & Zeng, M. (2009). Value-for-money strategies for recessionary times. Harvard Business Review, 87, 66-74.

Wong, E. M., Ormiston, M. E., & Haselhuhn, M. P. (2011). A face only an investor could love: ceos' facial structure predicts their firms' financial performance. Psychological Science, 22, 1478-1483.

Zebrowitz, L. A. (1997). Reading faces: Window to the soul? Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Zebrowitz, L. A., & Montepare, J. M. (2005). Appearance DOES matter. Science, 308, 1565-1566.