In the present article it is argued that aggression or more specifically, taking revenge has contrary to previous research findings not only negative (i.e., aggression increasing) but also positive (i.e., aggression reducing) consequences. Whereas aggressive thoughts and aggressive behavior might be reduced by taking revenge, negative feelings most likely increase. Thus, a fine-grained analysis of the consequences of revenge is warranted.

In September 2004, Ameneh Bahrami turned down a marriage proposal of Majid Movahedi – not for the first time. This rejection had severe consequences for Ameneh: One evening Majid ambushed her and poured sulfuric acid into her face. Her face, her eyes, her lips and her tongue were burned. Ameneh´s face is now disfigured and she is blind in both eyes. Upon a plea from Ameneh, the perpetrator Majid was sentenced to the same punishment: He will be blinded in both eyes from acid drops – most likely by Ameneh herself, who asked for the right to carry out the punishment herself. Many interesting psychological questions arise from this case as well: Would Ameneh feel better after she dropped acid into the eyes of Majid? Would it help her to think less of him and of harming him, and ultimately help her overcoming this traumatic event? In the following, we will address these questions from a psychological point of view, which boil down to the more general issue of whether taking revenge is beneficial or harmful for the avenger: Does it feel good to take revenge? Does it reduce aggression in general?

We assume that the effects of aggression are not inevitably good or bad as suggested by traditional views on aggression. The notion of Catharsis, the idea that aggressing reduces aggression in the future, has a long history in Philosophy and (Social)-Psychology alike. In Philosophy, already Aristotle claimed that typically negative feelings expressed in a drama cause the audience to re-experience these feelings: this leads to a vicarious expression of their emotion and therefore to a reduction of this emotion in the audience. In Psychology, Lorenz (1974), for example, assumed in his instinct model that organisms constantly build up aggressive energy. Since the organism cannot endlessly accumulate aggressive energy it needs to be released at some point. After the energy has been released – typically through an aggressive act – subsequent aggression is less likely to occur. Consequently, any aggressive act (such as taking revenge) is cathartic and can reduce subsequent aggression and might, in this sense, be beneficial. Thus, from this point of view, aggression is inevitable and moreover necessary at some point to restore psychological balance. In sharp contrast, the General Aggression Model (GAM, Anderson & Bushman. 2002), one of the most prominent current models on aggression in (Social)-Psychology, assumes that aggression is not inevitable. More specifically, aggression occurs through an interplay of situational and personality factors. These, however, do not necessarily lead to aggression. If aggression nevertheless occurs, it fosters inevitably subsequent aggression through, among other mechanisms, increasing negative affect and activating thoughts related to aggression. Thus, according to this model, aggressing increases future aggression.

We suggest that a fine-grained analysis of aggression is needed to account for this complex phenomenon. In the following, we will attempt such an analysis. We will look at different psychological variables known to influence aggression: cognition, affect, and behavior. Contrary to past and current reasoning about aggression, we claim that aggression can either increase or decrease future aggression. We will argue that revenge has different effects on cognition, affect, and behavior. Whereas hostile affect increases, aggressive thoughts and even aggressive behavior can be reduced upon taking revenge. We will apply our analysis to the example of Ameneh Bahrami to illustrate – admittedly in a speculative manner – how different psychological processes might be differently affected by taking revenge.

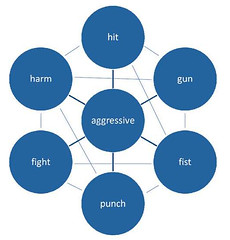

We will begin our analysis with cognitions related to aggression; more specifically, with aggressive thoughts that are activated in memory. It is known that thoughts are one determinant of behavior (see Bargh, Chen, & Burrows, 1996; Dijksterhuis & Bargh, 2001). Aggressive thoughts that are activated in memory typically lead to behavior that is congruent with the activated concepts. To give an example, reading of the recent heavyweight championship prize fight and thereby reading and thinking of aggression, can increase the likelihood of aggressive acts (see Phillips, 1983).

Figure 1: A simplified schematic depiction of an associative network