Donald Trump has lost the support of many conservatives, a problem that may be explained by his lack of conscientiousness. This trait is more characteristic of conservatives than liberals, which makes it a critical trait for conservative candidates. In the case of Trump, a lack of conscientiousness has likely repelled conservative voters who would otherwise vote Republican in the presidential election. Nevertheless, Trump maintains some support among conservatives, and this support may arise from his right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation.

Trump is not only losing, but losing by a large margin, an indication that he is not only unpopular among moderates, but also among a fair share of conservatives. This lack of conservative support is evident in some solidly right-wing states. In South Carolina, for instance, where 43% of people identify as conservative, and Georgia, where 40% do so, the conservative candidate usually wins. However, Trump is likely to win these two states by small margins.

Why is the Trump campaign hemorrhaging conservative voters in the US, who have not been this skeptical of a Republican Party candidate since Barry Goldwater? A number of factors play into his unpopularity, and while psychological research on conservatives cannot tell us about all of them, it can explain at least one.

Trump does not appear to be conscientious. Conscientiousness is one of the “Big Five” personality traits. Each personality trait in this set of five is considered big because it compasses smaller facets, and in the case of conscientiousness, these smaller facets are conventionality, reliability, industriousness, order, impulse control, and virtue (Roberts, Chernyshenko, Stark, & Goldberg, 2005). (Virtue, in this case, refers to the belief that one should be honest, moral, and charitable.) Everyone is conscientious to some degree, but there is enough variability that some people are markedly conscientious while others are markedly impulsive, unconventional, unreliable, and so on.

Political psychologists have found that conscientiousness differentiates conservatives from liberals, with conservatives (on average) being higher in conscientiousness. To make this less abstract, consider a study by Dana Carney and colleagues (Carney, Jost, Gosling, & Potter, 2008) of the dorm rooms and offices of conservatives and liberals. On average, a conservative person was likely to have these things in their space: an event calendar, a book of postage stamps, sewing thread, an iron, an ironing board, and a laundry basket. Coders who were hired to examine photographs of these spaces also rated conservatives’ spaces, on average, as more well-lit, fresh, neat, and clean. These are obvious manifestations of industriousness, order, and impulse control.

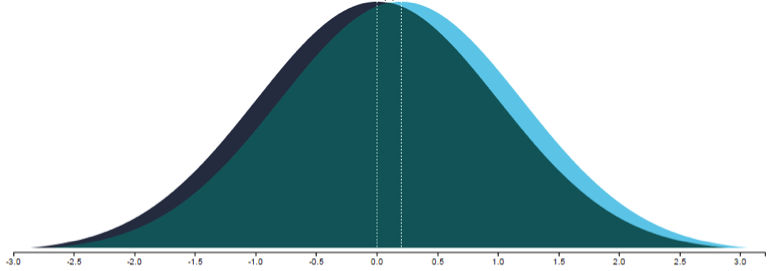

The majority of studies on politics and personality have found results linking conscientiousness with political conservatism, but the correlation is small, so many conservatives and liberals are similarly conscientious (Sibley et al., 2012).

However, the small difference still matters. In the illustration, think of the left, darkly shaded hump as liberals and the right, light blue hump as conservatives, with the dark green representing where liberals and conservatives overlap. Conscientiousness is on the X-axis, meaning that negative numbers indicate how much less conscientious someone is compared to the average person while positive numbers indicate how much more conscientious someone is compared to the average person. Despite the overlap, it’s evident that as you move to the left on this axis, the proportion of liberals to conservatives (dark blue to light blue) gradually favors liberals. At the tip you find a small range of people extremely low in conscientiousness, all of whom are likely liberal.

If you’re trying to fit in with a conservative crowd, here’s one obvious piece of advice: be conscientious. Show some discipline and restraint, or, at the very least, try not to exhibit a deficit in these areas. As a rule, conservative voters will be attracted to conscientious candidates, and repulsed by impulsive ones because people are socially attracted to those who are similar to them (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). In politics specifically people vote for candidates whose personality is similar to their own personality and to the ideology of their party (Caprara & Zimbardo, 2004).

In the case of Donald Trump, the impulsiveness and lack of restraint are so noticeable that numerous conservatives have pointed to those characteristics are reasons to shun Trump. The National Review ran a set of 22 short essays by prominent conservatives who oppose Trump. At least half drew attention to Trump’s intemperance: “at least Ross Perot kept his craziness confined mostly to private matters” (David Boaz), “a boor” (Mona Charen), “restraint is clearly not in his vocabulary or his character” (Steven F. Hayward), “Trump says he would order the military to kill the families of terrorists . . . a direct violation of the most basic laws of armed conflict” (Michael Mukasey), and “the id is supposed to be balanced by an ego and a superego ... Trump is an unbalanced force” (John Podhoretz).

One would expect liberals to impugn Trump differently, drawing attention to Trump’s racism and sexism, but even liberals are pointing to his impulsivity. When Hillary Clinton had the convention floor, her criticism of Trump built up to this line: “A man you can bait with a tweet is not a man we can trust with nuclear weapons.”

As this punchline shows, opponents can easily portray Trump as a threat, a maniac whose recklessness will cause an immediate disaster.

According to some social scientists, the most significant psychological feature underlying conservatism is sensitivity to external threats (Hibbing, Smith, & Alford, 2014). This makes Trump particularly repellent. In fact, conscientious people become more conservative when a nation is under systemic threat, which partially explains the link between those traits (Sibley et al., 2012).

Given human frailty, every conservative candidate is likely to have some flaws, but in many cases these flaws do not appear directly threatening. In the past fifty years, the U.S. has had Republican presidents who have variously been senile, clumsy, doltish, and paranoid. Though unappealing, these characteristics convey unreliability, not explicit danger. Only two candidates—Goldwater and Trump—have shown a level of impulsivity that allowed their opponents to portray them as direct threats. Goldwater came across as impulsive because he seemed overly keen on attacking the Soviet Union militarily. He was portrayed as a harbinger of nuclear war, and this, among other reasons, caused him to lose in a landslide. Trump is not only sanguine about nuclear war, he also expresses other forms of imprudence that Republican national security experts have evaluated as direct threats to American safety. Moreover, he has derided Gold Star families and retired members of the military, an institution that defends America against threats.

Given that Trump is the embodiment of an impulsive and dangerous person, it might be surprising that he became the Republican candidate at all. One likely reason for his success is that he appeals to voters who believe that people on the margins of society, such as Muslims and immigrants, deserve to stay at the margins. This attitude, which psychologists call right-wing authoritarianism, is not exclusively conservative, but it is more commonly found among conservatives than liberals (Duckitt, Bizumic, Krauss, & Heled, 2010). Trump also promulgates the idea that hierarchical social arrangements are desirable—some classes of people deserve to be at the top and others deserve to be at the bottom. This attitude is called social dominance orientation, and it is also not exclusively conservative, but more common among conservatives (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). Some conservatives, like Reagan, believe that we live in a just society that already has this hierarchy and we simply need to maintain it. Trump, however, is an anti-elitist populist (Oliver & Rahn, 2016). He proposes to upend the status quo and restore a once regnant hierarchy. This is still an appeal to social dominance orientation, albeit one that Americans have not recently seen. These appeals to right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance likely caused enough Republican-leaning voters who share authoritarian and social dominance attitudes to overlook both his formerly liberal attitudes and his problematic temperament.

Does Trump’s behavior hold a lesson for people outside politics? Trump epitomizes the characteristics that Aristotle posited as the source of misery. In The Nicomachean Ethics, a treatise on human flourishing, Aristotle explained that we all begin life with a tendency toward impulsivity. To lead a virtuous, flourishing life, we must develop the ability to exert self-control. This enables us to stay upright at the “golden mean,” which lies between tempting but dangerous alternatives. Courage is the golden mean between cowardice and rashness; liberality the mean between stinginess and wastefulness; proper pride the mean between insincere humility and vulgarity. Although psychologists generally avoid discussions about the golden mean (here’s an exception), their findings align with Aristotle’s basic thesis about conscientiousness being necessary for flourishing (Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006). Although his inherited wealth and its attendant privileges have cushioned him against some harsh consequences, Trump has ultimately come face to face with the tragedy of his impulsivity and generally low conscientiousness. His current attempt at flourishing seems destined to fail because it is obvious to many US voters, but not to him, that he cannot steer his own ship.

References

Caprara, G. V., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2004). Personalizing politics: A congruency model of political preference. American Psychologist, 59(7), 581–594. http://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.581

Carney, D. R., Jost, J. T., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Political Psychology, 29(6), 807–840. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00668.x

Duckitt, J., Bizumic, B., Krauss, S. W., & Heled, E. (2010). A tripartite approach to right-wing authoritarianism: The authoritarianism-conservatism-traditionalism model. Political Psychology, 31(5), 685–715. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00781.x

Hibbing, J. R., Smith, K. B., & Alford, J. R. (2014). Differences in negativity bias underlie variations in political ideology. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 37(3), 297–307. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X13001192

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

Oliver, J. E., & Rahn, W. M. (2016). Rise of the Trumpenvolk: Populism in the 2016 Election. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667(1), 189–206. http://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216662639

Ozer, D. J., & Benet-Martínez, V. (2006). Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 401–421. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190127

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741–763. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741

Roberts, B. W., Chernyshenko, O. S., Stark, S., & Goldberg, L. R. (2005). The structure of conscientiousness: An empirical investigation based on seven major personality questionnaires. Personnel Psychology, 58(1), 103–139. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00301.x

Sibley, C. G., Osborne, D., & Duckitt, J. (2012). Personality and political orientation: Meta-analysis and test of a threat-constraint model. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(6), 664–677. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.08.002