You’ve probably heard the saying, “birds of a feather flock together.” While you might know this to be true intuitively, it has also been verified by social and psychological science. The tendency for people to prefer similarity has been studied for many years in social psychology, where it is called the ‘similarity-attraction effect’ (Byrne, 1971; 1997). Sociologists also study a similar concept, which they refer to as ‘homophily,’ and ‘homogamy’, or ‘assortative mating’ in the case of mate selection (Mare 1991). Psychologists who study similarity-attraction and sociologists who study homophily are for the most part interested in the same questions: Why and how do similar people end up clumping together. However, the ways they approach the topic tend to differ: Psychologists tend to consider micro-level personal preferences (e.g., Do people actually prefer similar people to dissimilar people for friends?), and sociologists tend to look at the end result of similar people grouping together or marrying one another in society at large (e.g., Do similar people tend to live in the same places, and if so, what does this mean for society?). In this article we (a psychologist and sociologist) combine psychological and sociological perspectives to think about how preferences for similarity can interact with social-ecological factors such as relational mobility (the number of opportunities there are for people to form new and end old relationships) and residential choice (the ability for people to choose where they live) to create different outcomes, both for relationships and for society at large.

Cultural differences in similarity between friends, and the importance of mobility

Just how do we know that people have a preference for similarity, and how pervasive is it? Classic research in psychology has used a method called the ‘bogus stranger paradigm’ (Byrne, 1971) to examine the impact of similarity on how much participants report liking a stranger in the laboratory. Typically, participants in these studies will be shown the responses of a survey purportedly filled out by a stranger they will allegedly meet. In fact, the stranger does not exist, and the survey responses were systematically generated with similarity to the participant’s own responses. Studies using the bogus stranger paradigm have shown that increasing the level of similarity between oneself and the bogus stranger makes it more likely that the participant would want to meet and befriend the stranger.

Sociologists, in turn, have found a great deal of evidence demonstrating that similar people do tend to ‘flock’ together on a societal level (Mare, 1991; McPherson, Smith-Lovin & Cook, 2001). People are more likely to befriend, marry, and live in neighborhoods with people who are similar to themselves, especially in terms of their income, political ideologies, and level of education.

So just how pervasive is this preference for similarity? It turns out that people around the world, from both Western and non-Western countries, show a preference for similarity in bogus stranger paradigms (Byrne et al., 1969; Fujimori, 1980; Gudykunst & Nishida, 1984; Okuda, 1996; Porwal & Jain, 1985; Yabrudi & Diab, 1978). Even chimpanzees, our close primate cousins, tend to spend more time with others who have similar personalities (Massen & Koski, 2014)! It seems that, broadly speaking, people (and chimps) who have things in common really do seem to gravitate toward one another.

Even though people around the world seem to generally prefer similarity in people they spend time with, at the same time other studies show that there are substantial cultural differences in just how likely people are to actually end up in relationships with similar others. For instance several studies have found that East Asians tend to have friends who are less similar to themselves compared to North Americans (Igarashi et al., 2008; Satterwhite, Feldman, Catrambone, & Dai, 2000; Uleman, Rhee, Bardoliwalla, Semin, & Toyama, 2000), leading some to wonder whether the similarity-attraction effect exists in Japanese culture at all (Heine, Foster, & Spina, 2009). How could it be that, even though people all around the world supposedly prefer similarity, people in Japan aren’t choosing similar friends?

Even though people around the world seem to generally prefer similarity in people they spend time with, at the same time other studies show that there are substantial cultural differences in just how likely people are to actually end up in relationships with similar others. For instance several studies have found that East Asians tend to have friends who are less similar to themselves compared to North Americans (Igarashi et al., 2008; Satterwhite, Feldman, Catrambone, & Dai, 2000; Uleman, Rhee, Bardoliwalla, Semin, & Toyama, 2000), leading some to wonder whether the similarity-attraction effect exists in Japanese culture at all (Heine, Foster, & Spina, 2009). How could it be that, even though people all around the world supposedly prefer similarity, people in Japan aren’t choosing similar friends?

To explain this apparent puzzle, Schug Yuki, Horikawa, and Takemura (2009) proposed that cultural differences in self-friend similarity could be explained not as a result of cultural differences in the preference for similarity (although cultural differences in the extent of this preference may occur), but rather by relational mobility, or the opportunities that societies provide individuals to form new relationships (Schug, Yuki & Maddux, 2010; Yuki & Schug, 2012). So, even if you prefer to become friends with someone like you, if you live in a society with low relational mobility you might end up choosing your friends based on who is available, rather than based on your personal preferences. And, a number of studies have found that relational mobility tends to be a lot lower in Japanese society than it is in North American society (See Yuki & Schug, 2012 for a review). So, breaking with the tradition of psychologists (who tend to think more about individual preferences than about social context, more typically in the realm of sociology), the researchers suspected the difference in similarity between friends in North America and Japan might be due to differences in the society, rather than underlying cultural differences in individual preferences.

They asked groups of American and Japanese participants to report their preferences for similarity in a potential new friendship partner and also asked them to estimate the similarity between their close friends and themselves for a number of traits. They found that both American and Japanese participants preferred a similar person as a friend. But the extent to which they reported how similar they were to their existing friends depended on how much relational mobility they felt existed in their social environment: the lower the perceived relational mobility, the lower the similarity among their friends. In fact, when they looked at Japanese and American participants who perceived their social network as having the same level of relational mobility, there was no cultural difference in how similar they and their close friends were—participants in both countries who felt there were more chances to form new and leave old relationships felt their friends were more similar. It seems like people in Japan and the US aren’t so different after all-- Americans just seem to have more opportunities to choose new (and discard old) friends.

The size of the pool matters

The ability to choose from a larger number of choices gives people more chances to put their preferences for similarity into practice. This was highlighted by a study conducted by Bahns, Pickett, and Crandall (2012). They approached pairs of students who happened to be hanging out either at a large university or a small college campus, and asked them to fill out a survey. They found that pairs from the small college campus tended to be less similar to each other than pairs from the large university campus, suggesting that the larger pool from which students selected their friends allowed them to choose a more similar friend. This result is even more impressive when you think about the fact that the large university overall had a more diverse group of students.

Another study conducted by sociologist Ishiguro (2011) examined the levels of actual similarity between pairs of close friends in Japan. He found that you could use the number of people an individual had met in the past year, and the number of people they knew overall, to predict how similar the friends were in the pairs. The more acquaintances, the more similar the friends were. Research on homogamy has also shown that people who broaden their search to extend outside of narrow ethnic and religious communities are more likely to find a similar mate in terms of personality than those who do not (Ahern, Cole, Johnson, & Wong, 1981; Guttman, Zohar, Willerman, & Kahneman, 1988). It seems like widening the size of the pool you choose from translates to higher levels of similarity. The important thing to remember is that the effects of similarity are brought about by personal choices—random mobility should not have an impact on the similarity among people. In this sense, our choices about whom we associate with, combined with our preference for similarity, is what causes levels of similarity between friends and couples to increase. Next, we will discuss implications of these choices for society at large.

The dark side of the preference for similarity

So far we’ve established that people tend to prefer similar others, but whether or not you can actually end up in relationships with similar people depends on the social environment, and how easy it is in that environment to choose people to form relationships with. That is, the higher the relational mobility of the environment (the more choices one has to form new and leave old relationships), the more chances there are for people’s preferences to translate into actual choices.

This might sound like a good thing, but a lot of other research suggests that there are unfortunate societal level consequences to people getting what they want in societies high in relational mobility. For example, people who are highly desirable will have no trouble meeting and forming relationships with others who are highly desirable. While this might be good for them, this means that people who are a little less desirable might have a much harder time with relationships in high-mobility societies. Thus relationships have the potential to be much more stratified socially, with those who are more highly desirable winning out.

One example of this social stratification can be seen in educational homogamy. Since the 1960s, the tendency for people to marry others with the same level of education has been increasing in the US (Mare 1991, Schwartz & Mare 2005). Now more than ever, people are marrying and having children with those of similar educational backgrounds.

Now you might be wondering whether this increase in educational homogamy is due to an actual increase in the preference for similarity in educational attainment, or due to some other factor, such as the fact that more women are attending college these days. The answer appears to be a bit of both. One commonly accepted explanation is that because women’s access to education and opportunities in the workforce have improved, the education and economic status of women is now a relevant factor for men to consider in selecting their mates (Oppenheimer 1988, Sweeney 2002), compared to when it was still relatively rare for women to go to college or join the workforce.

Obviously, educational attainment has a big impact on occupational status and income. What this means is that now more than ever, couples are either very well-off (both earning a high income) or not at all (both earning low incomes). The uncomfortable result of this is that socioeconomic inequality among households for our generation is much higher than it was when households had spouses of mixed educational levels. In fact, economists have shown that rising income inequality in the US can be explained by people marrying people with similar levels of educational attainment (Greenwood, Guner, Kocharkov, & Santos, 2014). If anything, it appears that if it weren’t for people marrying people with similar levels of education, economic inequality is the United States would be falling instead of rising!

Preferences for similarity and residential segregation

The same preference for similarity can also have implications for segregation and fragmentation of the neighborhoods in which we live. Social scientists have been studying segregation of neighborhoods, based on factors such as ethnicity, race, and income for decades (e.g., Massey & Denton, 1988). How did cities in the US get so segregated? In the case of ethnic and racial segregation, one common explanation is ‘white flight’ or tipping (Grodzins, 1957). When “undesired” minorities move into a predominantly white neighborhood, the theory is that whites tend to pack up and leave.

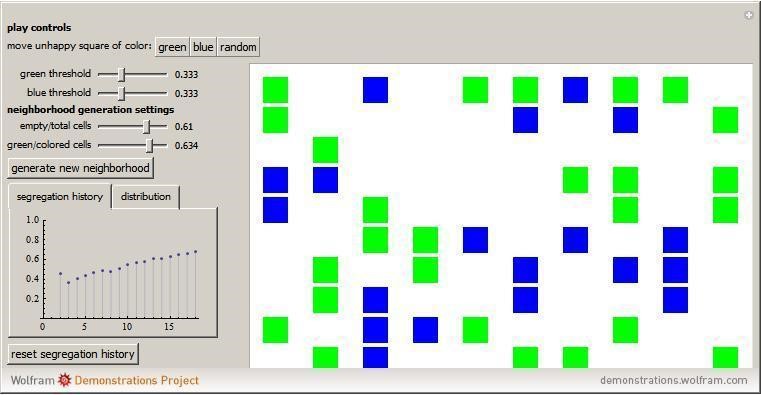

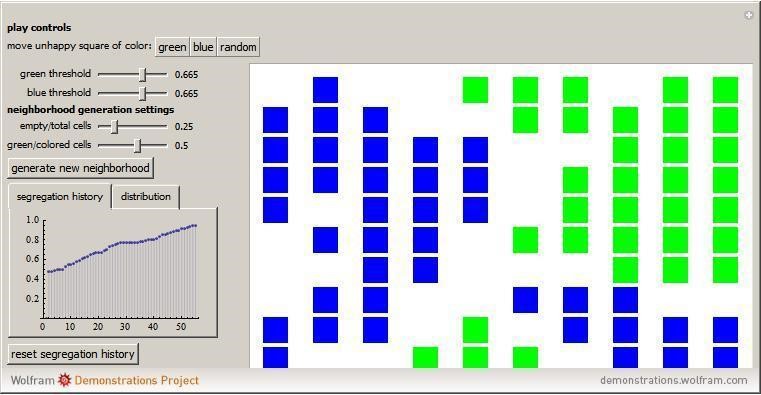

But what if our seemingly benign preference for similar others is once again the culprit here? Economist and Nobel laureate Thomas Schelling (1971) demonstrated through a simple agent-based simulation model that this indeed may be the case. Schelling created a grid-like structure where the cells represented housing opportunities, and agents of different types would occupy these cells with the opportunity to relocate. The ‘free-will’ of these simulated agents worked along a threshold mechanic. At each step of the simulation, the agent would take a look at the other agents who “lived” in the adjacent cells. If enough of these agents were of a different type, the agent would more to a new neighborhood, or in other words, they would relocate to a random empty cell that was surrounded by more similar agents.

Schelling found that when agents preferred cells that were surrounded by at least one-half of similar agents, striking patterns of segregation would occur. In fact, eventually the system would achieve close to the mathematically maximum amount of segregation possible given the parameters. Schelling also found that uneven populations would enhance the segregation. When one population outnumbered the other 3:1 or 4:1, the minority population would very quickly form a large homogenous cluster. This was because the low initial numbers of cells containing similar others caused the minority to relocate aggressively in the early stages of the simulation.

More recently, researchers have tried to update Schelling’s original model to accommodate the more complex nature of real neighborhoods. The fashionable thing to do now is use continuous preference functions, where the probability of moving isn’t black or white, but comes in shades of grey. Bruch and Mare (2006; 2009) argue that these functions generate less segregation compared to Schelling’s threshold functions. However, Van de Rijt, Siegel, and Macy (2009), found a disconcerting result: when simulated agents were sensitive to how the composition of their neighborhoods were changing in terms of the number of agents similar to themselves, the simulation could become very segregated once again, even with built-in parameters for diversity and tolerance.

Race isn’t the only factor by which neighborhoods can become segregated based on people’s decisions to relocate to live near similar others. For instance, some investigations have proposed that residential mobility may be increasing the political polarization of the United States, as individuals tend to move to places which match their political ideologies. In his book The Big Sort, Bill Bishop (2009) argues that ideologically-based migration is leading to a more polarized society. More recently, Motyl and colleagues (2014) showed that people whose ideologies did not fit with community were more likely to want to relocate to a new neighborhood. The same thing appears to happen with wealth, as wealthy couples tend to relocate to expensive metropolitan areas, inadvertently leading to rural areas becoming poorer (Costa & Kahn, 1999). These investigations suggest that greater residential mobility, combined housing choice (choices in where one relocates to), can translate into higher levels of homogeneity within neighborhoods in wide number of domains.

Fig 1. The progression of residential segregation over time, in the Schelling model of residential segregation. You can try experimenting with a demonstration of Schelling’s simulation yourself. (Requires Wolfram cdf player plugin)

http://demonstrations.wolfram.com/SchellingsModelOfResidentialSegregation/

Overall, our preference to form relationships and live alongside similar others can interact with our social environment in a number of ways. The amount of opportunities we have to form new relationships or move from residence to residence can translate into higher levels of similarity among friends and romantic partners in society, and our choices based on preferences for similarity can, on an aggregate level, end up creating a fragmented and stratified society. This might be an important thing to think about when you decide whom you associate with in the future. While it would certainly be unacceptable (at least in modern, Western societies) to dictate who can marry whom, who can befriend whom, or what neighborhood certain types of people should or should not be able to move to, understanding that our choices have implications for the nature of society at large is very important. Like the agents in Schelling’s simulations, we are all embedded in a complex system where the tides flow in both directions: our environment can affect and constrain our choices in friendships, and in turn we can affect our environment with our relationship choices themselves. Something to think about the next time you consider making a new friend or moving to a new neighborhood!

References

Ahern, F. M., Cole, R. E., Johnson, R. C., & Wong, B. (1981). Personality attributes of males and females marrying within vs. across racial/ethnic groups. Behavior Genetics, 11(3), 181–194.

Bahns, A. J., Pickett, K. M., & Crandall, C. S. (2012). Social Ecology of Similarity Big Schools, Small Schools and Social Relationships. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15(1), 119–131. doi:10.1177/1368430211410751

Bruch, E. E., & Mare, R. D. (2006). Neighborhood Choice and Neighborhood Change. American Journal of Sociology, 112(3), 667-709.

Bruch, E. E., & Mare, R. D. (2009). Preferences and Pathways to Segregation: Reply to Van de Rijt, Siegel, and Macy. American Journal of Sociology, 114(4), 1181-1198.

Byrne, D. (1997). An Overview (and Underview) of Research and Theory Within the Attraction Paradigm. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 14(3), 417–431. doi:10.1177/0265407597143008

Byrne, D. E. (1971). The attraction paradigm [by] Donn Byrne. New York: Academic Press.

Byrne, D., Griffitt, W., Hudgins, W., & Reeves, K. (1969). Attitude Similarity-Dissimilarity and Attraction: Generality Beyond the College Sophomore. The Journal of Social Psychology, 79(2), 155–161. doi:10.1080/00224545.1969.9922403

Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S., Gonzaga, G. C., Ogburn, E. L., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2013). Marital satisfaction and break-ups differ across on-line and off-line meeting venues. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(25), 10135–10140. doi:10.1073/pnas.1222447110

Costa, D. L., & Kahn, M. E. (1999). Power Couples: Changes in the Locational Choice of the College Educated, 1940-1990 (Working Paper No. 7109). National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w7109

Fujimori, T. (1980). Effects of attitude similarity and topic importance on interpersonal attraction—with relation to the dimensions of attraction. Japanese Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 20(1), 35–43.

Greenwood, J., Guner, N., Kocharkov, G., & Santos, C. (2014). Marry Your Like: Assortative Mating and Income Inequality. American Economic Review, 104(5), 348–53. doi:10.1257/aer.104.5.348

Grodzins, M. (1957). Metropolitan Segregation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gudykunst, W. B., & Nishida, T. (1984). Individual and cultural influences on uncertainty reduction. Communication Monographs, 51(1), 23–36. doi:10.1080/03637758409390181

Guttman, R., Zohar, A., Willerman, L., & Kahneman, I. (1988). Spouse similarities in personality traits for intra- and interethnic marriages in Israel. Personality and Individual Differences, 9(4), 763–770. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(88)90065-7

Heine, S. J., Foster, J.-A. B., & Spina, R. (2009). Do birds of a feather universally flock together? Cultural variation in the similarity-attraction effect. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 12(4), 247–258. doi:10.1111/j.1467-839X.2009.01289.x

Igarashi, T., Kashima, Y., Kashima, E. S., Farsides, T., Kim, U., Strack, F., … Yuki, M. (2008). Culture, trust, and social networks. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 11(1), 88–101. doi:10.1111/j.1467-839X.2007.00246.x

Ishiguro, I. (2011). Attitude homophily and relational selectability : An analysis of dyadic data [in Japanese]. Japanese Journal of Social Psychology, 27(1), 13-23.

Mare, R. D. (1991). Five Decades of Educational Assortative Mating. American Sociological Review, 56(1), 15–32.

Massen, J. J. M., & Koski, S. E. (2014). Chimps of a feather sit together: chimpanzee friendships are based on homophily in personality. Evolution and Human Behavior, 35(1), 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.08.008

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1988). The Dimensions of Residential Segregation. Social Forces, 67(2), 281–315. doi:10.1093/sf/67.2.281

McLeod, P. L., Lobel, S. A., & Cox, T. H. (1996). Ethnic Diversity and Creativity in Small Groups. Small Group Research, 27(2), 248–264. doi:10.1177/1046496496272003

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

Okuda, H. (1996). Asymmetry in interpersonal attraction and its relation to the effects of similarity and dissimilarity. Japanese Journal of Social Psychology ( Before 1996, Research in Social Psychology ), 12(2), 97–103.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1988). A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology, 563-591.

Porwal, N. K., & Jain, R. K. (1985). Attitudinal similarity as factor of interpersonal attraction. Indian Psychological Review, 28(1), 24–29.

Satterwhite, R. C., Feldman, J. M., Catrambone, R., & Dai, L.-Y. (2000). Culture and perceptions of selfother similarity. International Journal of Psychology, 35(6), 287–293. doi:10.1080/002075900750048003

Schug, J., Yuki, M., Horikawa, H., & Takemura, K. (2009). Similarity attraction and actually selecting similar others: How cross-societal differences in relational mobility affect interpersonal similarity in Japan and the USA. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 12(2), 95–103. doi:10.1111/j.1467-839X.2009.01277.x

Schug, J., Yuki, M., & Maddux, W. (2010). Relational Mobility Explains Between- and Within-Culture Differences in Self-Disclosure to Close Friends. Psychological Science, 21(10), 1471 –1478. doi:10.1177/0956797610382786

Schwartz, C. R., & Mare, R. D. (2005). Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography, 42(4), 621-646.

Sweeney, M. M. (2002). Two decades of family change: The shifting economic foundations of marriage. American Sociological Review, 132-147.

Uleman, J. S., Rhee, E., Bardoliwalla, N., Semin, G., & Toyama, M. (2000). The relational self: Closeness to ingroups depends on who they are, culture, and the type of closeness. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3(1), 1–17. doi:10.1111/1467-839X.00052

Van de Rijt, A., Siegel, D., & Macy, M. (2009). Neighborhood Chance and Neighborhood Change: A Comment on Bruch and Mare. American Journal of Sociology, 114(4), 1166-1180.

Yabrudi, P. F., & Diab, L. N. (1978). The Effects of Attitude Similarity-Dissimilarity, Religion, and Topic Importance on Interpersonal Attraction among Lebanese University Students. The Journal of Social Psychology, 106(2), 167–171. doi:10.1080/00224545.1978.9924167

Yuki, M., & Schug, J. (2012). Relational mobility: A socioecological approach to personal relationships. In O. Gillath, G. Adams, & A. Kunkel (Eds.), Relationship Science: Integrating Evolutionary, Neuroscience, and Sociocultural Approaches (pp. 137–151). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.