In a recent murder case, a 6-year-old girl claimed immediately upon arrival of the ambulance and police to have witnessed her father stabbing her mother (Brackmann, Otgaar, Sauerland, & Jelicic, 2014). Does such an account really reflect what happened and should it be used as evidence in court?

In criminal cases, it is important to decipher whether eyewitness statements are credible or not. Indeed, erroneous eyewitness statements can have severe consequences, such as wrongful imprisonment and waste of resources. The delineation of eyewitness accounts is relevant because such accounts often constitute the only piece of evidence in a police investigation or a trial (Ceci & Bruck, 1993). Technical evidence, such as DNA samples, is frequently absent. Hence, it is vital to know whether witnesses provide an accurate reflection of what happened or whether their statements have been infected by memory distortions, so-called false memories.

Comparing child witnesses to adult witnesses, the knee-jerk response among many legal professionals is that children’s testimonial accuracy is inferior to that of adults (e.g., Brainerd, Reyna, & Ceci, 2008). According to this view, children’s memory functions less optimally than that of adults, making them more prone to memory errors, such as false memories. This default assumption has far-reaching effects on jurisdiction. Specifically, when both an adult and a child provide a report of what purportedly occurred, more weight might be placed on the statement of the adult.

Intriguingly, however, recent evidence shows that under certain circumstances, this assumption is untenable. In recent years, there has been an upsurge in new research on the reliability of children’s testimony (e.g., Brainerd, 2013), revealing that adults, and not children, are sometimes the most susceptible to memory illusions. This developmental pattern has been dubbed developmental reversal.

In the current paper, we address the relevance of these new findings to the legal domain. Importantly, we focus on eyewitness testimonies and the possibility that they are infected with faulty recollections. Of course, in the legal arena, other types of evidence might be relevant, such as identification performance. Research indeed shows that there are developmental differences between children’s and adults’ identification performance (Havard, 2013). Discussing these particularities is beyond the scope of this paper.

We therefore start with a short historical overview of early studies on children’s testimony and legal cases involving child witnesses. These early findings led to the conclusion that children’s eyewitness accounts can easily be infected with false memories. Subsequently, we discuss the formation of false memories by demonstrating that depending on certain factors, false memories may increase with age. We describe recent experimentation indicating that even forensically-relevant false memories follow an age-related increase. Finally, we consider the practical value of these new findings.

The vulnerability of children’s testimony

Early research has pointed out weaknesses in children’s memory and its implications for the legal field (e.g., Loftus, 2005). The underlying question was whether and under which circumstances children are capable of giving an accurate report of what they have witnessed. Among the first researchers who systematically and experimentally analysed children’s memory in a way that has implications for the legal context were Binet (1900) and Varendonck (1911) at the beginning of the twentieth century (as cited in Ceci & Bruck, 1993). They found that the type of questioning has an influence on children’s answers. Specifically, invitations to freely recall what had happened led to the most accurate responses, whereas (mis)leading questions merely elicited conformal answers (Binet, 1900). In Varendonck’s field study, 17 of 22 children even reported details about an unknown suggested person. Subsequent studies adapted the methods used by these pioneers. A review of studies published between 1979 and 1992 comparing the suggestibility of young children vs. older children and adults found a decrease in the formation of false memories with age in 83% of the studies (Ceci & Bruck, 1993). Even though individual differences exist, young children were generally found to be more vulnerable to suggestive interviews and erroneous information than older children and adults (Bruck & Ceci, 1999).

The research reported above was, among others, stimulated by legal cases in which the authenticity of children’s testimony was doubted (e.g., Ceci & Bruck, 1993). Examples are the American day care child sexual abuse cases of Kelly Michaels and the McMartin Preschool that occurred in the late 1980s. These two cases had in common that the police interviews with the children were conducted in a highly suggestive manner merely suited to confirm the interrogators’ prevailing hypothesis of the factual occurrence of abuses, but not to obtain truthful and accurate testimony (Schreiber et al., 2006). Interviewers’ techniques included (1) the introduction of new information that had not previously been mentioned by the child witness, (2) positive reinforcement of answers that were in accordance with police's prior expectations and beliefs of what had happened, (3) showing scepticism towards answers that were not in accordance with those prior expectations and beliefs, (4) applying conformity pressure by referring to statements made by other children, and (5) invitations to speculate about the alleged events (Schreiber et al., 2006).

Importantly, such cases were not exclusively American. In Germany, the Wormser- and the Montessori-trials are notable examples of cases in which children’s statements were likely the result of suggestive interviewing techniques (Schade & Harschneck, 2000). Furthermore, in the Netherlands, the alleged ritual abuse of about 50 children between the ages of three to 11 by strangers in the city Oude Pekela was highly debated (Jonker & Jonker-Bakker, 1997). Notably, all these cases started with a vague initial suspicion that evolved into serious and precise allegations with life-changing consequences for the suspect.

The question can be raised whether children’s vulnerability as eyewitnesses is due to memory impairments or adults creating an atmosphere of speculation and rumour transmission. Important in this branch of research is Principe, in whose studies children watched a magic show where the rabbit-out-of-hat trick failed (Principe & Schindewolf, 2012). The children were then assigned to different groups among which one group overheard an adult conversation about why the trick failed and how the rabbit escaped. This group and another group of their classmates were the rumour groups. After a two-week-delay, their statements were compared to a group that actually witnessed a rabbit running around after the magic show. Intriguingly, no differences were present between these groups on reporting the loose rabbit (Principe, Kanaya, Ceci, & Singh, 2006). Thus, children can remember a witnessed event, but false memories might be due to their vulnerability to elaborate on rumours.

The bottom-line message emerging from the legal cases and the related research was that false memories are more prevalent among children than adults, and hence children’s testimonial accuracy is inferior to that of adults. However, this view has recently been challenged by a series of studies showing age-related increases in false memories. For example, younger children were less likely to infer and elaborate on the loose rabbit rumour when only clues (i.e., nibbled carrot) suggested its escape than older children (Principe, Guiliano, & Root, 2008). These diametrical findings challenge the child’s supposed inability to make credible statements. It even suggests that not children but adults are more susceptible to certain false memories.

The strength of children’s testimony

To understand how such seemingly conflicting patterns can occur, with children being sometimes more and other times less vulnerable to false memories than adults, it is imperative to differentiate between different types of false memories. The formation of false memories can be caused by internal and external factors (Brainerd, Reyna, & Ceci, 2008). Externally-driven false memories are also called suggestion-induced false memories. These are frequently elicited experimentally using a classical misinformation paradigm originally introduced by Loftus, Miller, and Burns (1978).

This paradigm contains three main phases: (1) participants are exposed to an event (e.g., a slide show of a car accident), (2) they are confronted with misinformation (a question suggesting that the car stopped in front of a stop sign even though it was a yield sign), and (3) they have to answer final memory questions concerning the content of the original event. Research has shown that a significant minority of participants incorporate the misinformation into their memory reports and develop false memories. Moreover, children are considered to be more prone to this misinformation effect than adults (Loftus, 2005).

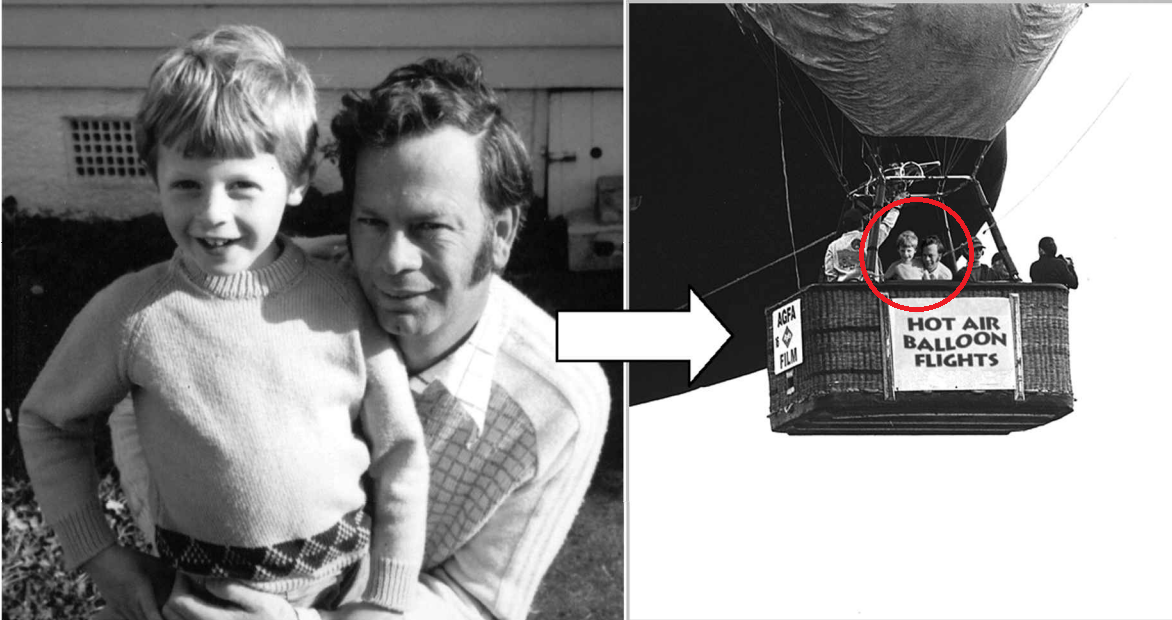

Indeed, researchers have shown that it is possible to implant false memories for entire events. For instance, participants provided vivid and detailed descriptions of a hot air balloon ride they actually never experienced in response to the presentation of a manipulated photograph (see Figure 1; Wade, Garry, Read, & Lindsay, 2002). In children, this misinformation effect can be obtained for highly implausible events, such as an UFO-abduction (Otgaar, Candel, Merckelbach, & Wade, 2009). Again, children were more susceptible to implanted false memories than adults.

Internally-driven false memories, on the other hand, emerge without external influence. They are called spontaneous false memories. A robust method to study this phenomenon is the Deese/Roediger-McDermott (DRM)-paradigm (Deese, 1959; Roediger & McDermott, 1995). In a typical DRM experiment, participants are instructed to study word lists. The words semantically relate to each other (e.g., young, female, dolls, dress, cute, hair) while one critical related word is missing (i.e., girl). In final memory tests, adult participants falsely “remember” this critical word with rates comparable to those of the presented words (Roediger, Watson, McDermott, & Gallo, 2001).

In contrast to suggestion-induced false memories, spontaneous false memories are more likely to emerge in adults than in children (Brainerd et al., 2008). Theoretically, this developmental pattern has been predicted by an influential memory theory called the Fuzzy-trace Theory (FTT; Brainerd, Reyna, & Ceci, 2008). FTT postulates that the memory for an event is stored in two traces: (a) the verbatim trace and (b) the gist trace. The verbatim trace captures specific details of an event. When seeing a knife (see Figure 2), the verbatim information would be “silver object with a blade and black handle”. In addition to this, adults automatically extract the gist of an event which includes the underlying meaning of an experience. Consequently, the presence of a weapon is stored as the gist representation. While verbatim information can be assessed as soon as the senses function properly (e.g., seeing), the extraction of gist information relies on knowledge that an individual has accumulated over the years. During development, people augment their knowledge and therefore their performance in gist extraction increases (Reyna & Kiernan, 1994). Astonishingly, this advantage in gist extraction leads to an age increase in false memories. The older children get and the longer the delay between encoding and retrieval is, the more they rely on gist information. If specific verbatim information has to be remembered, it can happen that this information is no longer available. Thus, false memories occur when gist representation leads to erroneous inferences. For example, for the question “How did the thief threaten the victim?” reliance on the gist might lead to the erroneous answer “with a pistol”.

Evidence supports this view, with children being less vulnerable to the formation of false memories than adults for meaning-connected experiences (see Otgaar, Howe, Peters, Smeets, & Moritz, 2014). More specifically, studies employing the DRM paradigm have found that younger children exhibit lower recall and recognition rates of the critical, non-presented words than older children (e.g., Brainerd, Reyna, & Zember, 2011). Thus, a developmental reversal can be found in spontaneous false memories. As a consequence, it is not likely that in the case that was described in the introduction, the 6-year-old girl produced a spontaneous false memory.

So, based on the above, we find that suggestion-induced false memories are more likely to occur in children than in adults, whereas spontaneous false memories are more prevalent among adults than children. A series of experiments showed that even suggestion-induced false memories can increase with age (Otgaar, Howe, Smeets, Brackmann, & Fissette, 2014). This developmental reversal in suggestion-induced false memories occurs when participants are misled about related but non-presented details that share the same underlying gist representation. In these experiments, younger children, older children, and adults were presented with a video of a robbery. During the video, several details were presented (e.g., the culprit), but several related details were left out (i.e., a weapon). Then, participants received misinformation about these missing related details. When using this procedure, adults and older children were more likely to retrieve the gist information and to accept the related misinformation than younger children. This shows that even forensically-relevant conditions that originally fuelled the assumption of children being exceptionally susceptible to false memories can lead to significant age increases in false memories.

Consequences

Whereas early findings suggested that children’s accounts are generally more vulnerable to memory distortions, more recent research predicts that not children but adults are particularly susceptible to forming false memories in highly meaning-connected situations. This new view has been supported by work using the DRM paradigm, showing that adults more often than children report the critical, non-presented words that are related to the presented word list. An age increase in spontaneous false memories has also been demonstrated in more ecologically valid contexts. In eyewitness identification research, for example, younger children were found to be less likely to misidentify an innocent bystander as being the thief than older children (Ross et al., 2006). Furthermore, evidence indicating that adults can have higher false memory rates than children even for false memories induced by suggestion is accumulating (Connolly & Price, 2006; Otgaar, Howe, Smeets, et al., 2014).

What are the consequences of these findings? Should child testimony be refused or favoured as evidence in court when the statement of an adult is available? Neither the idea that children always tell the truth nor the one that child testimony is generally afflicted by memory distortions seem to be adequate rules of thumb. On the one hand, children are capable of giving highly accurate testimony (Bidrose & Goodman, 2000), but on the other hand, they might give faulty accounts due to the formation of false memories. Even though faulty eyewitness accounts are possible in children, these findings do not imply that false memories are absent in adults. As pointed out, under conditions in which adults display greater knowledge of a standard scheme of occurrence than children, false memories are more likely to be present in the adult age group. A thorough analysis of each individual case is therefore imperative to assess the credibility of a child’s statement. It is necessary to establish how and under which circumstances allegations were first brought up and how they developed over time. In light of developmental reversals the widespread assumption of legal practitioners believing that an adult’s statement is nearly always more accurate and trustworthy than that of a child is untenable and needs to be corrected.

Paradoxically, children might be more reliable in situations that are very familiar to adults, but not to children. Especially when there is reference to a unique occurrence and the child makes a spontaneous utterance without previous pressure or influence, their statements should not be left aside. Consequently, in the aforementioned murder case, no external influences provide reason to doubt the 6-year-old girl’s identification of her father as the perpetrator.

References

Bidrose, S., & Goodman, G. S. (2000). Testimony and evidence: A scientific case study of memory for child sexual abuse. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 14, 197–213. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(200005/06)14:3<197::AID-ACP647>3.0.CO;2-6

Binet, A. (1900). La suggestibilité [The suggestibility]. Paris: Schleicher Freres.

Brackmann, N., Otgaar, H., Sauerland, M., & Jelicic, M. (2014). When children are the least vulnerable to false memories: A true report or a case of autosuggestion? Manuscript submitted for publication.

Brainerd, C. J. (2013). Developmental reversals in false memory: A new look at the reliability of children’s evidence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22, 335–341. doi:10.1177/0963721413484468

Brainerd, C. J., Reyna, V. F., & Ceci, S. J. (2008). Developmental reversals in false memory: A review of data and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 343–382. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.343

Brainerd, C. J., Reyna, V. F., & Zember, E. (2011). Theoretical and forensic implications of developmental studies of the DRM illusion. Memory & Cognition, 39, 365–380. doi:10.3758/s13421-010-0043-2

Bruck, M., & Ceci, S. J. (1999). The suggestibility of children’s memory. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 419–439. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.419

Ceci, S. J., & Bruck, M. (1993). Suggestibility of the child witness: A historical review and synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 403–439. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.403

Connolly, D. A., & Price, H. L. (2006). Children’s suggestibility for an instance of a repeated event versus a unique event: The effect of degree of association between variable details. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 93, 207–223. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2005.06.004

Deese, J. (1959). On the prediction of occurrence of particular verbal intrusions in immediate recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58, 17–22. doi:10.1037/h0046671

Havard, C. (2014). Are children less reliable at making visual identifications than adults? A review. Psychology, Crime & Law, 20(4), 372–388. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2013.793334

Jonker, F., & Jonker-Bakker, I. (1997). Effects of ritual abuse: The results of three surveys in The Netherlands. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21, 541–556. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00011-2

Loftus, E. F. (2005). Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory. Learning & Memory, 12, 361–366. doi:10.1101/lm.94705

Loftus, E. F., Miller, D. G., & Burns, H. J. (1978). Semantic integration of verbal information into a visual memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 4, 19–31. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.4.1.19

Mason, M. A. (1995). The child sex abuse syndrome: The other major issue in State of New Jersey v. Margaret Kelly Michaels. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 1, 399–410. doi:10.1037/1076-8971.1.2.399

Otgaar, H., Candel, I., Merckelbach, H., & Wade, K. A. (2009). Abducted by a UFO: Prevalence information affects young children’s false memories for an implausible event. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23, 115–125. doi:10.1002/acp.1445

Otgaar, H., Howe, M. L., Peters, M., Smeets, T., & Moritz, S. (2014). The production of spontaneous false memories across childhood. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 121, 28–41. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2013.11.019

Otgaar, H., Howe, M. L., Smeets, T., Brackmann, N., & Fissette, A. (2014). Changing developmental trends in suggestion-induced false memories. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Principe, G. F., Guiliano, S., & Root, C. (2008). Rumor mongering and remembering: How rumors originating in children’s inferences can affect memory. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 99, 135–155. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2007.10.009

Principe, G. F., Kanaya, T., Ceci, S. J., & Singh, M. (2006). Believing is seeing how rumors can engender false memories in preschoolers. Psychological Science, 17, 243–248. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01692.x

Principe, G. F., & Schindewolf, E. (2012). Natural conversations as a source of false memories in children: Implications for the testimony of young witnesses. Developmental Review, 32, 205–223. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2012.06.003

Reyna, V. F., & Kiernan, B. (1994). Development of gist versus verbatim memory in sentence recognition: Effects of lexical familiarity, semantic content, encoding instructions, and retention interval. Developmental Psychology, 30, 178–191. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.30.2.178

Roediger, H. L., & McDermott, K. B. (1995). Creating false memories: Remembering words not presented in lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 21, 803–814. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.21.4.803

Roediger, H. L., Watson, J. M., McDermott, K. B., & Gallo, D. A. (2001). Factors that determine false recall: A multiple regression analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 8, 385-407.

Ross, D. F., Marsil, D. F., Benton, T. R., Hoffman, R., Warren, A. R., Lindsay, R. C. L., & Metzger, R. (2006). Children’s susceptibility to misidentifying a familiar bystander from a lineup: When younger is better. Law and Human Behavior, 30, 249–257. doi:10.1007/s10979-006-9034-z

Schade, B., & Harschneck, M. (2000). Die BGH-Entscheidung im Rückblick auf die Wormser Missbrauchsprozesse. Konsequenzen für die Glaubhaftigkeitsbegutachtung aus der Sicht des psychologischen Gutachters und des Strafverteidigers [The Federal Court of Justice decision in retrospect of the Wormser abuse trials. Consequences for the credibility assessment from the perspective of the psychological expert and the defence lawyer]. Praxis der Rechtspsychologie, 10, 28-47.

Schreiber, N., Bellah, L. D., Martinez, Y., McLaurin, K. A., Strok, R., Garven, S., & Wood, J. M. (2006). Suggestive interviewing in the McMartin Preschool and Kelly Michaels daycare abuse cases: A case study. Social Influence, 1, 16–47. doi:10.1080/15534510500361739

Varendonck, J. (1911). Les témoignages d’enfants dans un procès retentissant [The testimony of children in a famous trial]. Archives de Psychologie, 11, 129-171.

Wade, K. A., Garry, M., Read, J. D., & Lindsay, D. S. (2002). A picture is worth a thousand lies: Using false photographs to create false childhood memories. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9, 597–603. doi:10.3758/BF03196318